CBC Radio: Payday-style lenders do brisk business thanks to ‘desperation borrowing,’ debt counsellor says

Posted January 30, 2024

Ottawa has proposed lowering the criminal rate of interest to soften the blow

Jolene Chateauneuf was just trying to avoid getting evicted.

It was 2021, and she was short $1,500 for the rent on her apartment in Princeton, B.C., where she was living at the time. So she took out a rapid loan from a payday-style lender and gave the money to her landlord.

Rapid loans are sometimes referred to as instalment loans, to differentiate them from traditional payday loans, which — as the name implies — are paid back in one lump sum when the borrower’s paycheque arrives.

In the last few years, rapid loans have become common as most provinces cracked down on predatory payday loan practices, prompting alternative lenders to instead offer larger loans with longer payment periods.

The first few times Chateauneuf picked up a rapid loan, she was able to pay it back, she told Cost of Living. But when she got behind on payments, and they were sent to collection agencies, she’d apply for new loans to cover the shortfall so she could make sure her family had a roof over their heads.

When she fell behind with one lender, it was easy enough to find another.

“I’d just Google ‘instalment loans. No credit check.’ … Like, it’s super, super easy. And you’ll get the money that day, like, within half a day at least.”

Today the 28-year-old mother of two young children is sinking under about $50,000 in debt from rapid loans, combined with student loans and car payments.

“The biggest issue was the interest rate, which is 46.9 per cent…. So basically you’ve got to pay back your whole loan plus another half of it, which is impossible,” said Chateauneuf, who is currently living in Calgary but hoping to return to Princeton, where the rents are lower and the pay she can get as a health-care assistant is higher.

“My credit score used to be perfect, and now it’s, like, 395, which is crazy. I have so many things in collections because I just couldn’t pay the instalment loans, which put my credit card behind. And I’ve always been good with my credit card, too, and I just couldn’t keep up with anything.”

Ottawa proposes lowering criminal interest rate

The federal government has now proposed regulatory changes that would lower the criminal rate of interest from the equivalent of 47 per cent annual percentage rate (APR) to 35 per cent APR.

But credit counsellors and poverty activists say addressing the root causes — income that hasn’t kept pace with the cost of living and lack of access to fair credit for low-income earners — are the only things that will help prevent people from turning to whatever loan options are available, legal or otherwise.

“People are desperation borrowing, and this is one notch short of loan-shark stuff,” said credit counsellor Scott Terrio, manager of consumer insolvency at Hoyes, Michalos & Associates in Toronto.

Terrio said he and his colleagues have “a front-row seat to consumer debt.” In the last two or three years, he said, they’ve seen a “dramatic increase” in people whose debt troubles stem from rapid loans.

In 2022, 53 per cent of insolvencies filed by the firm included at least one rapid loan, up from 21 per cent in 2011.

Courtney Mo, director of community impact for Momentum, a Calgary-based charity that helps people train for employment opportunities and manage their money, said the issue of instalment loans has recently become “unignorable.”

“We discovered that so many people living on a low income were and are taking out instalment loans and other types of fringe loans to make ends meet,” she said.

In June 2023, a survey from the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada, a federal government agency that enforces consumer protection legislation, found that 3.6 per cent of respondents from a representative sample of Canadians had used an online lender or payday loan company during the survey period. The survey was conducted online and by phone between August 2020 and December 2022, among a representative monthly sample of about 1,000 Canadians aged 18 years or older.

Every province except Manitoba has lowered the maximum legal cost of a payday loan in the past seven years, in an effort to protect borrowers from predatory lending practices. In Alberta, that happened in August 2016, when Bill 15, An Act to End Predatory Lending, came into effect.

When that cut into the profit margins of fringe lenders, Mo said, they almost immediately moved to promote and sell instalment loans instead of payday loans. “And instalment loans are usually much larger, dollar value, like sometimes $5,000 or more. Whereas payday loans can be, you know, $500, $1,000 maybe.”

Terrio said the lenders give out these loans knowing the borrower already has existing debt.

“So the person is already carrying $30,000 in credit card debt or something — and it’s there on the credit report, right, for all to see — and here you go. Here’s another 15 grand or 10 grand at 48 per cent interest.”

Alternative lenders say they help the ‘unbanked’

In an email to CBC News, the Canadian Consumer Finance Association, which represents alternative lenders, said they charge these rates because they take on a lot of risk by providing unsecured loans to people who can’t otherwise access capital due to poor credit or low income. The group added that up to 25 per cent of borrowers default on these loans.

The statement also said that more than one-quarter of Canadians are “unbanked.”

“This means that while the majority have a bank account, they do not qualify for a credit card, line of credit, loan or mortgage.”

Terrio said these lenders are effectively playing the odds. “Because I guess most people pay them back, or at least pay them back long enough for them to make all kinds of money.”

But changing the rules on how much interest alternative lenders can charge won’t do enough to fix the reasons people go to them in the first place, he said.

At the root of things, Terrio said, people are really facing an income problem rather than a debt problem, “because a lot of this wouldn’t be in place if people were paid properly for what they do, and you could afford to live a decent life like everybody did 20, 30 years ago.”

Once-in-a-generation inflation, interest rate hikes, the COVID-19 pandemic and a housing affordability crisis have made it harder for so many people to get by, he said.

While those problems are complex to address, regulatory changes that make it harder for consumers to qualify for these high-interest loans could help prevent people from getting in too deep, Terrio said.

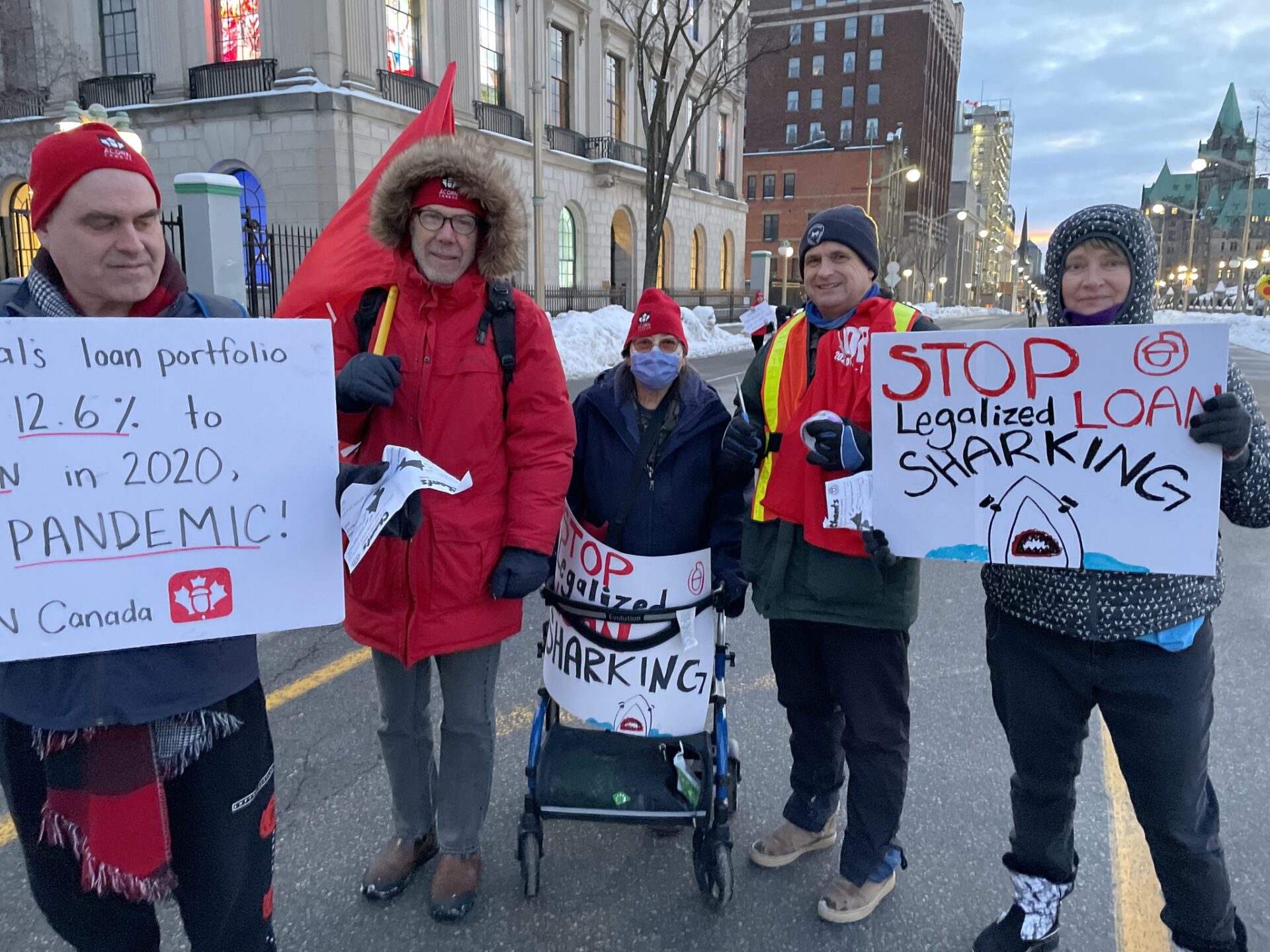

ACORN, a national anti-poverty group, is pushing for the big banks to make more financial products available to low-income people and for the federal government to create a fair credit benefit, administered by a non-profit or a community development organization, so that low- and moderate-income people are not forced to rely on predatory lenders.

The association that represents Canadian credit unions put out a report in 2021 on ways that some of its members have developed payday loan alternatives for the “financially excluded.”

Alternative lenders ‘everywhere you look’

In the part of Mississauga, Ont., where Marcia Bryan lives, there’s no shortage of places to get a rapid loan.

“You take a step across the street, there’s about four, five, six of them,” she said. “Everywhere you look, they are right there, and where I live is most of the lower-income families.”

Bryan said when she sees people lining up, “I just want to take a bullhorn and just get them to get a hell out of there, because they are vulnerable. I’ve been there, so I know what it’s like.”

A mother and grandmother who lives on payments from the Ontario Disability Support Program and a small amount of money she makes catering on the side, she took out an instalment loan when she needed to help family back in Jamaica.

A couple of years ago, Bryan used a debt consolidation service to help dig herself out of $12,000 in debt, mostly from rapid loans, after realizing her high monthly payments were going to interest alone, while the balance never went down.

Still, she said she understands why people are walking through the brightly coloured doors of alternative lenders.

“The way the economy is right now, when you get paid, it’s either your rent or groceries,” Bryan said, noting that people feel forced to go to alternative lenders because “the bank is not lending you anything.”

****

Article by Brandie Weikle for CBC Radio