Toronto Life: There Will Be Blood

Posted January 30, 2024

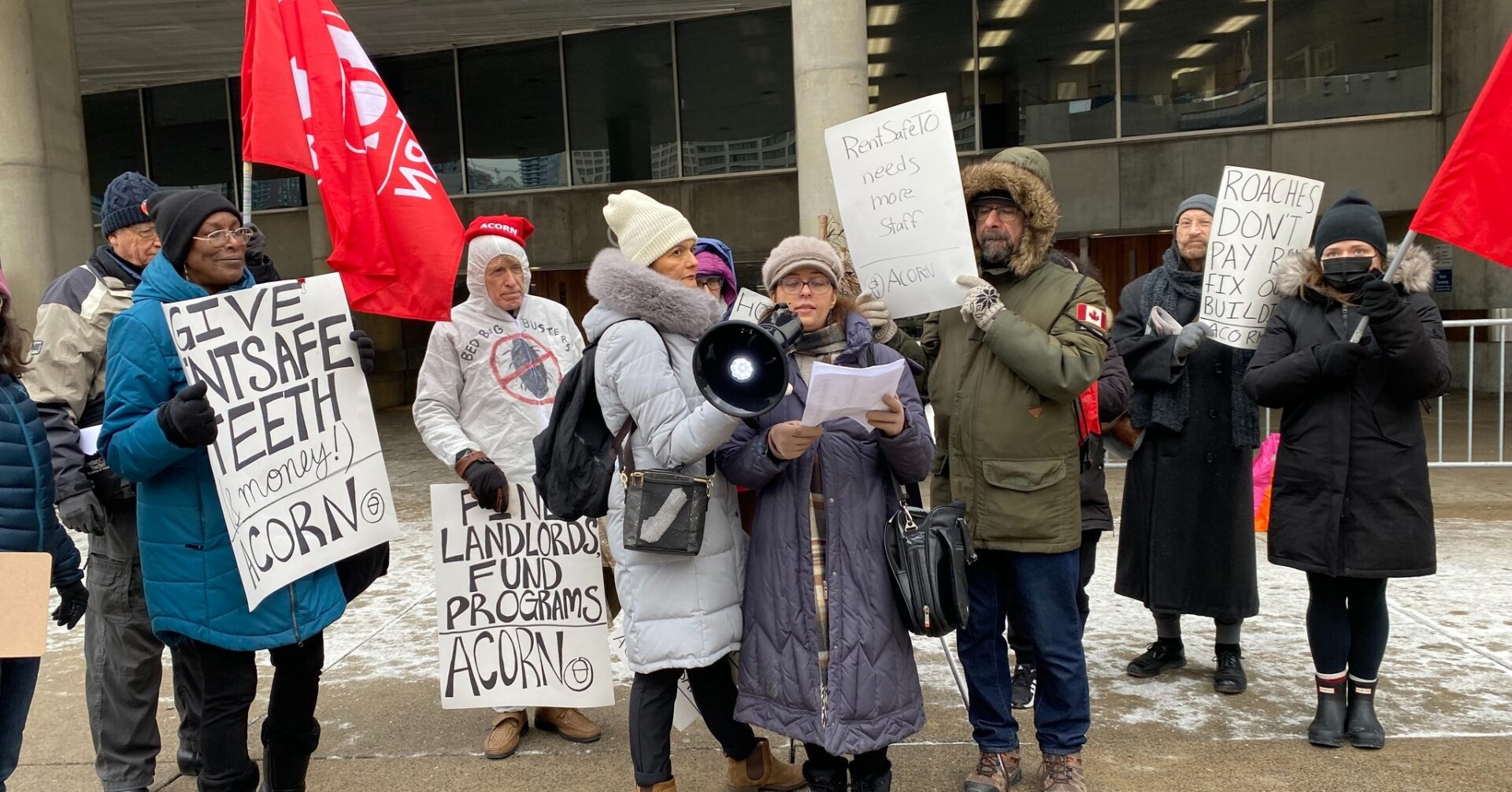

East York ACORN members Christena Abbott and Sasha Shashkova features in this Toronto Life article are organizing their neighbourhood to fight back and win pest control! By getting their neighbours together these ACORN members have gotten their landlords to do pest treatments!

Bedbugs are—no exaggeration—everywhere in Toronto: our libraries, offices, schools, hospitals, hotels, transit and homes. Inside the always expensive, often traumatic, probably futile battle to eradicate the bloodsucking parasites that are ruining our lives

In the spring of 2017, I moved into a grubby basement apartment in the Beaches. When I went to view it, I could already tell that it would be perpetually damp—it smelled faintly of turned earth and musty sock. It was depressingly dark. There was no place for my desk, and I would have to store my cat’s litter box in the shower. Yet I was desperate to move out of the apartment I shared with my soon-to-be-ex-boyfriend, and I couldn’t afford much else on my freelancer income. Besides, the space did have a few things going for it. I liked the industrial-boho aesthetic of its exposed-brick wall and concrete floors, and there was a washer and dryer squeezed into the bathroom. Plus, the location: I could leave my cave for the sandy, sunny shores of the lake any time I wanted. In a moment of willful delusion, I told myself I could make it work.I couldn’t. Despite the $300 dehumidifier I splurged on, my apartment remained stubbornly soggy. Then, in my first winter there, a couple of days before New Year’s Eve, the pipes froze. When the plumber finally arrived, his strategy was to hack into the drywall—raining debris on my floors and furniture—until he found the offending pipe; it took days for my landlord to (badly) patch the gaping holes. After that, ants streamed in, forming undulating lines across my bookshelves, my kitchen counters, my bed. I stocked up on traps and diatomaceous earth, orchestrating the colony’s demise with the glee of a serial killer. My relief was fleeting. One day that summer, I arrived home to find an anonymous note in the mailbox. It helpfully informed me that a few houses on the block were battling rats—rats!—and that the rodents could squeeze through the smallest of cracks.

All to say that, when a one-bedroom opened up in a friend’s building a short bus ride away, I begged him to put in a good word for me. I’d had enough of my basement misadventures. I didn’t think to question it when the building’s supervisor told me I could come look at an apartment that week, but not the vacant one—it was being renovated. I was too enamoured of the idea of having a bathtub and reasonably sized windows. I also knew my friend had happily lived in the building for years. What could go wrong?

Once approved, I signed the lease without hesitation. At first, my gamble appeared to pay off. If anyone had been watching the moment I first walked into my unit, they might have thought I was auditioning for a Colgate ad. I couldn’t stop grinning as I inspected my brand-new appliances, tiles, countertops; basked in the warm sunlight blazing through the wall-to-wall windows; inhaled the aroma of Lysol, not dampness. The place was huge, mine and perfect. Or so I thought.

I had a month, October, in which my leases overlapped. Once my tiny basement apartment became overrun with boxes, I decided to buy a cheap air mattress, haul over some essentials and stay in my new place for the week leading up to moving day. A couple of nights later, I sat with the air mattress pushed against the wall, blissfully working on my laptop, my fat tabby sprawled at my feet. I felt a tickle along my forearm before I saw it: a metric ton of ick contained in something the size and shape of an apple seed. I had just enough time to wonder, Bedbug? before I saw the others. One inching its way along my laptop. Another three on my pillow. Oh god. A dozen emerging from under the baseboards. All slowly, methodically marching toward me. I screamed, of course. Then I smashed every bug I could spot, scooped their corpses into a Ziploc bag and put them in the freezer, slamming the door shut. Evidence. Next, I began to thoroughly, entirely freak out.

I spent hours googling photos of bedbugs and their bite patterns. I texted my friend in the building. He gently suggested I was imagining things—he’d never had any problems—but also not-so-gently suggested I wasn’t welcome to come over until I was certain. After that, I threw out a painting I’d thrifted earlier that day, just in case. Then, in a fit of caution, the pillow I’d seen the bugs on. I put everything I could into the building’s dryer, cycling it through for hours on the hottest setting. Yet, instead of sleeping in my freshly laundered sheets, I stuffed them in a garbage bag that I tightly knotted. My logic: any remaining bugs would suffocate or at least be stuck inside. Any attempt to sleep, I soon discovered, was futile. The bare air mattress was cold and uncomfortable, and every time my eyelids drooped shut, the thought of bugs feeding on me startled me awake. In the morning, I phoned my superintendent. His voicemail said he was on vacation, so I left a stammering message asking the junior super, who was filling in, to call me back.

He eventually did, and as I relayed my worry, I was surprised by how unsurprised—even chill—he seemed. The building could send someone tomorrow or the next day to look, he told me, unconvinced by my panic. I sent a photo of my trapped enemies to the best-reviewed extermination company in my area, and when they wrote back suspecting, yes, bedbugs, I asked for an immediate inspection, cost be damned. A couple of hours later, a sanguine dude in an exterminator suit confirmed that my apartment was infested. Not only that: he could tell that it had been recently treated. There was a chemical residue along the baseboards, and the crevices were bug graveyards. The building must have known long before I moved in that there was a problem. More bad news: the pests were as notoriously difficult to eradicate as I’d feared. My stomach sloshed. I had moved out of a nightmare apartment and into something somehow far worse.

My panic was part of a multi-millennia-long tradition of people freaking out over bedbugs. The earliest evidence of the critters living alongside us was unearthed at an Egyptian archeological site dating back some 3,350 years. They are believed to have then spread throughout the Roman Empire as a result of the Mediterranean shipping trade—after which people apparently began burning entire rooms, and sometimes buildings, to rid themselves of infestations. In 1730, the world’s first bedbug-control manual, A Treatise of Buggs, was published. Then came an era of new treatments: highly toxic chemical compounds, such as mercury chloride and arsenic dust, which people blithely applied even if it sometimes killed them too; fumigants by way of candlesticks dipped in sulphur, which could damage household items; and, later, hydrogen cyanide, which was also lethal to humans. Bedbugs were so ubiquitous by the 1800s that many London lodges advised their customers to get drunk if they wanted some sleep. It wasn’t until later in the 19th century that people began to successfully steam-treat rooms, but even then, burning down infested buildings remained a remedy up until the Second World War.

It took the introduction of DDT in the 1940s to finally tip the balance. The widespread use of the (extremely toxic) pesticide gradually obliterated the bedbug population throughout North America and Europe, and the pests remained rare in most cities long after Canada and the US banned DDT in the 1960s and ’70s. But, because bedbugs are the actual worst, the reprieve didn’t last. The tenacious insects resurfaced in the early 2000s: Venezuela got its first report in three decades; parts of the UK experienced a six-fold increase in a few short years; and compared with pre-resurgence levels, Australia saw a shudder-inducing rise of 4,500 per cent.

The situation was just as bad in Toronto, where reported cases jumped from just over 40 in 2003 to more than 1,500 in 2009. In response, the city created a bedbug super team of stakeholders—including representatives from various social services, housing providers, community organizations, landlord and tenant groups, and city divisions such as public health—to tackle the problem. In 2010, it asked the provincial government for roughly $15 million to create a five-year pest-control program. Instead, the province established a $5-million fund and invited 36 public health units across Ontario to apply for their piece of the pie. Toronto won a lump sum of $1.2 million. Once that ran out, the city’s bedbug-eradication efforts fizzled, and the program was eventually shuttered. It’s unlikely that one program would have halted the bedbugs’ city-wide takeover—they’re too resilient, too fertile, too insidious—but it was Toronto’s best chance of slowing them down. Without it, members of the public were left to battle the bugs on their own.

Today, the bugs are, without exaggeration, everywhere: residential buildings, hotels, office spaces, movie theatres, libraries, hospitals, universities, airports, public transit. This past October, the internet got the collective creeps when TikTok influencers began posting videos about bedbugs at Paris Fashion Week. A French health agency confirmed that at least 11 per cent of households in the country had been infested between 2017 and 2022 and that the number was on the rise. As people worried about the outbreak, Paris deputy mayor Emmanuel Grégoire offered his not-at-all-reassuring take: “No one is safe.” Someone in Toronto soon posted a video of what appeared to be a bedbug on public transit, and phantom itchiness and bedbug hysteria proliferated. (Those transit sightings were debunked-ish—one was probably a louse, another maybe a ladybug and the third inconclusive.) Next came a report of a bedbug hiding in a Toronto Public Library book; the TPL said there had been 12 confirmed cases of bedbugs at the city’s library branches between January and late October.

The team arrived to find a woman blanketed in bedbugs and unconscious, likely from blood loss

Bedbugs tend to be wherever we are, pest-control experts told me, and Toronto has a years-long record of being the most infested city in Canada. That’s in large part because of its size, population and general bustle; the city is a giant moving buffet. (For those who want to escape the dinner party: Halifax has the fewest infestations, whereas Vancouver ranks as the second-worst place, followed by Sudbury, Oshawa and Ottawa.) If the number of infestations in Toronto seemed scary a decade ago, we’re now in hell. The city’s community housing buildings alone had more than 17,000 infestations in 2022, accounting for a big chunk of its overall $3-million budget for pest control. Marginalized populations tend to be more susceptible to persistent outbreaks—it takes considerable money and effort to wipe out an infestation—but geographically speaking, bedbugs don’t discriminate. It doesn’t matter where you live or how expensive your home is. Hotspots can be found in both the east and west ends, the core and the suburbs. One expert I spoke to called Toronto’s bedbug problem an “epidemic.” I also heard the word “crisis” a lot.

As for why we’re seeing a resurgence now, experts aren’t entirely sure. But there are some sound theories. Antonia Guidotti has been an entomology technician at the Royal Ontario Museum since the 1990s. Part of her job is to respond to inquiries from both public health and the public, and in the early 2000s, like others in her field, she began seeing an uptick of people wondering whether the insects they’d found in their homes were bedbugs. (For the record, Guidotti likes all insects, but even she forbade people from sending her live specimens after receiving a tube full of skittering bedbugs.) She says the current resurgence of bedbugs likely has a lot to do with their ability to develop resistance to pesticides. See also: increased global travel and immigration, plus the bedbug’s prolific reproductive capabilities—one female will lay roughly five eggs a day, or up to 500 in her lifetime, which can be from five months to over a year. Bedbugs will hitch a ride anywhere they might find food. A few years ago, Guidotti was at a local hospital with her son when she spotted a bedbug. She scooped it up, dropped it in ethanol to drown and preserve it, and immediately alerted the staff. “Being an entomologist,” she says, “I carry a little vial of ethanol with me everywhere.”

Pest-control experts say there’s another big hurdle when it comes to stopping the spread: pride. Not everyone will alert their landlord or neighbours that they’ve found a possible bedbug for fear of judgment. Despite the fact that bedbugs are attracted to blood, not filth, there’s a pernicious belief that an infestation means a person’s home is dirty. Some people are afraid of that stigma; others simply don’t know what a bedbug looks like. Another persistently unhelpful myth is that bedbugs are too small to see. They’re not; they’re just diabolically good at hiding. By the time an infestation is noticeable, there can be hundreds of bugs inhabiting the baseboards, furniture, picture frames, carpets, wallpaper, electrical outlets and walls. Still, since they usually prefer to feed on us while we’re sleeping, a person may discover another tell-tale sign of the bugs—the dark, speckled stains of their excrement—before they see the bugs themselves.

People also rely too much on being able to see bites on their skin. Bedbugs are infamous for their bite pattern, three close dots often described as “breakfast, lunch and dinner.” The bites can actually look like everything from pimples to eczema, and more than 30 per cent of people don’t have a physical reaction at all. I did, and mine looked like a constellation of angry scarlet stars along my back. They also appeared days after I first saw the bugs; if I weren’t already on high alert, I’m not sure I would’ve immediately made the connection. Even when people do spot the bugs and report a sighting, their landlords, like mine, may be slow to act. If they treat the problem at all, many try to do so themselves, often ineffectively. Tactics include essential oils (totally useless), throwing out just your bed (they’re hiding elsewhere) or temporarily vacating your home until they die (mature bedbugs can go months without a meal). Chemical sprays on their own usually don’t work, and over-the-counter products beef up a bedbug’s resistance to the stronger pesticides often required to kill them. Meanwhile, the bugs keep spreading.

In November of 2023, driven by morbid curiosity and journalistic duty, I asked Dale Kurt, the GTA regional manager at Orkin Canada, if I could see some bedbugs. Orkin Canada started out in Mississauga in the 1950s as PCO Services. In 1999, it merged with the American outfit Orkin and became a big player in Canadian pest control. Its residential arm completes roughly 7,000 service calls in the GTA per month, ranging from prevention to control of many different types of vermin. None of those customers was keen on letting a journalist into their home to watch an eradication, so Kurt invited me to visit the bedbug research farm at the company’s headquarters. There, I could see some live bugs, learn the latest methods for exterminating them and hear more about how the company’s entomology department tests new products. As a bonus, I’d also get to meet one of their bedbug-detecting dogs, which I decided would be a nice break from all the nightmare fuel.

On the day I arrived, several technicians were out inspecting a university dorm for bedbugs—lecture halls and dorms across the city are common breeding grounds. TMU had a reported sighting last September at its Ted Rogers School of Management, one of several in recent years; a nasty 2018 case at U of T’s Trinity College prompted students to move out of the dorm. In a moment of temporary insanity, I asked to hear stories that would make me squeamish. Kurt, who graduated from Sir Sandford Fleming College’s pest-management program more than three decades ago and has been in the creepy-crawly biz ever since, merrily complied: once, he arrived home after visiting a particularly bad infestation and discovered dozens of live bugs stuck in the treads of his shoes. He promptly threw everything he was wearing in the dryer and steam-treated his truck.

Bernie Grafe, the GTA residential branch manager, heard us chatting and joined in. Grafe has also worked in pest control for decades and is the type of guy who unironically posts on LinkedIn—with pictures—that Orkin’s bedbug farm is “reason #453 as to why I love my job.” He told me about the time a team arrived to treat an elderly woman’s apartment and found her in a chair, blanketed in bugs and unconscious, likely from blood loss. Recently, Kurt added, they’d been called in to help get rid of bedbugs at a long-term care home in Collingwood. They treated the facility, but every few months, the bugs came back. After some investigative work, Kurt pinpointed the source of the infestation: a specific chair in the waiting room where one resident’s husband always sat. The man allowed Kurt and his team to inspect his home. There were bugs and blood everywhere. “You could have filmed a horror movie in there,” Kurt told me.

After that conversation, I was very ready to see how Kurt, Grafe and their team kill the parasites. Because bedbugs are excellent at hiding, a big part of the job is finding them. That’s where the dogs come in. (That said, once an infestation is bad enough, even humans can smell the bedbugs’ odour, which is sickly sweet.) I met an adorable Chesapeake Bay retriever named Watson, one of the three dogs Orkin has working in the GTA; a fourth is being trained to start soon due to spiking demand. Each dog lives with its handler, who trains them in their off-hours. Watson’s handler, Matt Rawson, conceals vials of live bedbugs around his home in what are called “blind hides” for Watson to find. I watched, impressed, as Watson quickly sniffed out two vials at the Orkin office. To keep the training bugs alive, Orkin employees sometimes suction the vials to their arms so the bugs can slurp their blood. Kurt offered to let me try, and I felt like a wimp when I declined—until Rawson told me he won’t do it either.

After the dogs indicate the presence of bedbugs, and depending on the level of infestation, technicians may vacuum first and then go in with a special steamer to get into nooks and crannies. The steam must blast at 125 degrees minimum to be effective, otherwise the bugs are essentially just getting wet. In brutal cases, a pest-control company will seal off a room, or an entire building, and bring in industrial heaters to roast the bugs. Such high heat will kill every stage, from egg to adult. The chemical pesticide that companies use in conjunction with all this is what’s classified as a pyrethrin (as well as its synthetic versions, pyrethroids). Derived from the chrysanthemum plant, pyrethrin compounds kill nearly all types of insects, including bedbugs, by attacking their nervous systems. Basically, the bugs twitch to death. (Perhaps I’m a monster for finding this delightful, but whatever.) At the same time, bedbugs are evolving to overcome these treatments. Their exoskeletons are becoming thicker and now have a waxy protective coating. Most devastatingly, they’ve started to develop a saline solution in their nerve endings to block the pyrethrin.

That’s where the research lab comes in. Or, as Orkin’s resident entomologist, Alice Sinia, calls it, the “fun room.” Like Guidotti, Sinia finds all insects, including bedbugs, fascinating. (I, on the other hand, find nothing about them redeeming—I mean, the males fertilize the females by a process dubbed “traumatic insemination.”) The lab is relatively small, with a few microscopes, a fridge and, notably, a terrarium of Mason jars filled with bedbug colonies. Each jar contains a few pieces of cardboard, providing the bugs with a comfortable place to hide. Sinia pulls a piece from Colony B, casually flicking a nymph that crawls up her thumb back into the jar, to show me the inner side of the cardboard, lined with bedbugs in various stages, all plump and deep crimson. When they’re not dining on Orkin staff, the bugs are fed cow’s blood from a device Sinia rigged up in the lab. The colony is where handlers get the bugs to train their dogs; it’s also used to test eradication methods from across the country.

On the lab’s computer monitor, Sinia pulls up photographs from a test of a pest-control product called Aprehend. In the simplest terms, it’s a biopesticide composed of fungal spores: it germinates on the bedbug, then colonizes its insides. The tests have gone well—the product is doing what it’s supposed to do, which isn’t always the case. There’s plenty of ineffective stuff on the market (though Sinia points out that shoddy application methods are frequently the bigger problem). That includes the aforementioned bedbug sprays sold in hardware stores, which often kill only the bugs you can see, as well as ultrasonic pest repellents, rubbing alcohol and kerosene.

Sinia ends the lab visit by showing me some live bedbugs under the microscope and explaining more about how they multiply so quickly. I watch as blood ripples back and forth in a bug’s body, being digested; after enough meals, it will grow, shedding its exoskeleton five times before it reaches adulthood. While other insects may socialize or build, bedbugs care only about sleeping, hiding, mating and eating (us). Sinia then asks if I want to see some dead bugs—not because she’s trying to indulge my hatred of the insects but because it’s easier to point out their biological characteristics when they’re not shuffling around. My answer: absolutely. I’m not shy about telling her, as well as Kurt and Grafe, who’ve joined us, that this is my favourite part of the visit. I snap a photo. There’s something comforting about the dead bug, still and translucent.

Back in 2018, after my own infestation was confirmed, I became obsessed with bedbugs—and not in a circa 1995 “Will Devon Sawa from Casper be my boyfriend?” kind of way. I spent hours scouring the internet for information, unable to stop even when I was supposed to be doing something else: working, packing my other apartment, sleeping. Mostly, I wanted to read stories of people who’d managed to get rid of the bugs for good. During this period of compulsive googling and corresponding mental decline, I was surprised to discover that bedbugs aren’t considered a public health risk. Although they’ve been found to harbour more than 40 infectious agents, including hepatitis B, HIV and a number of bacteria strains, they can’t transmit anything to humans. In other words, they’re considered annoying but not dangerous. Many experts I spoke with found this distinction wrong-headed: an infestation may not make a person physically ill, but it can have enormous mental and financial consequences.

People will go to extreme lengths to rid themselves of bedbugs, often defying logic. In some African countries, for example, people are ditching their malaria nets because they can be havens for bedbugs. My single-minded anxiety isn’t an uncommon reaction—for such a small bug, the weight of an infestation can be crushing. Mark Berber is an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto. While he’s never had bedbugs, he’s watched a close friend battle the parasites twice. He tells me a now familiar story: the friend’s building treated an infestation, but a few weeks later the bugs were back. Berber says it makes absolute sense that an infestation would take a massive toll on a person’s mental health. Stress, he adds, is the physical and emotional response to an event that’s considered threatening or challenging—and a bedbug infestation is both. There’s the financial cost, the trials of treatment, the risk of others’ judgment and the bugs themselves. An infestation may not be life-threatening, he explains, but that doesn’t mean it should be minimized. It can impair many aspects of a person’s day-to-day functioning, triggering anxiety, sometimes without remission; self-isolation out of fear of spreading the bugs to others; and understandably, a relentless worry that the bugs will return. One patient of Berber’s was so terrified of bedbugs that they became convinced they had them. The patient dressed in a hazmat suit and had their unit checked repeatedly. “People can talk about bedbugs as if they’re a minor irritation,” he says. “But the psychological impact can be devastating.”

Those who’ve had an infestation will often claim it gave them extreme anxiety or even traumatized them—enough to jump at a speck of lint on their bed—which seems over-the-top until it doesn’t. In one recently viral TikTok video, a 26-year-old entrepreneur named Cole Bennett responds to another TikToker who seems blasé about bedbugs. Bennett shares that he moved to Toronto at age 18, into a 12-unit building in the west end that housed a number of Airbnb rentals. After a suspected bedbug report, his building manager did the right thing and called in pest control to treat every single apartment. Four days later, Bennett still woke up covered in bedbug bites from his chest down. In the end, his building had to be tarped and treated for five weeks until the infestation was gone. He had to leave during the tarping and couldn’t take a single thing he owned; his building manager gave him new clothes. Bennett called it “the worst fucking thing” he’d ever been through. The video has since racked up two million views. One commenter remarked, “I had bedbugs in 2021. It broke me psychologically.” Another said, “People have no idea. They’re psychological warfare.” Eight years after his infestation, Bennett’s first question when he looks at a potential rental apartment is still about bedbugs. “It makes you paranoid,” he says.

Having recently lost it over what ended up being a stray coffee bean on my floor, I could relate. So could many of the people I spoke with for this story. One of them was a 75-year-old woman named Christine Abbott, whose building has had a persistent problem with bedbugs. Abbott moved into her unit in 2011, and five years later, when she saw her first bedbug, she didn’t know what it was. She learned soon enough. It took three treatments over 12 weeks for her apartment to get the all-clear. Preparing her apartment for the treatments wasn’t easy either: residents are required to move furniture away from their baseboards, get rid of clutter, and empty cupboards and closets. That’s a lot of work for anybody, but especially for someone like Abbott, who has arthritis, fibromyalgia and chronic pain. The first infestation cost her $2,200 because she had to buy a new mattress and box spring, among other items.

Those who’ve had an infestation will often claim it gave them extreme anxiety or even traumatized them

And a few years later, the bugs came back. She’s now suffered through three infestations, the most recent in December of 2022. The building’s property management firm, she says, typically sprays only the unit that reports the bugs, not the surrounding ones, leaving the infestation to sweep through the building. (Abbott’s upstairs neighbour, who has been infested twice, got rid of her couches and her bed and now sleeps on a cot rather than have to throw out furniture again.) Many buildings make the mistake of targeting a minimal number of units. While best practice dictates that surrounding suites be treated, this can be exorbitantly expensive. A lot of building managers cheap out—or they ostensibly don’t want to alarm other tenants. Many tenants will sound the public alarm; others will leave. Either way, the building can get the modern-day equivalent of a plague mark.

Bennett says his experience was so traumatizing that, even though his superintendent aggressively treated the problem, he still moved out. But, like many elderly people and others facing Toronto’s bonkers rental market, Abbott can’t afford to live anywhere else. Instead, she’s left to deal with increasingly disgusting situations: during the most recent infestation, bedbugs spread to her building’s laundry room. People would open the washer and dryer doors to find scattered bugs—dead and alive. These days, Abbott thoroughly checks her bed and pillow every night before she goes to sleep. “It’s always at the back of my mind,” she tells me. “I’m terrified.”

Infestations can have that effect on people. They are maddening, and our efforts to resist them are often futile. I spoke to another woman, Sasha Shashkova, who was living with her parents while her apartment was being treated. It was her second time fighting a bedbug infestation; the first was in 2019, when she was in her late 20s. That time, it took an entire year for the pests to be fully eradicated. She, her then-boyfriend and her cat were all living in the apartment. The bugs fed on all three of them—bedbugs treat us like a five-star meal, but they’ll also feast on domestic animals. When the pests returned in 2023, she was the only one living in the apartment. At first, she felt defeated—what was the point of fighting them if she couldn’t win? It didn’t help, she tells me, that she was going through a bout of depression. She briefly considered giving up but kicked her efforts into high gear after the bugs began biting her face.

Shashkova’s temporary paralysis is common: it could be embarrassment, exhaustion, a sense of helplessness or some combination of the three. Many of those who battle repeated infestations also tend to be among the city’s most financially marginalized, including the elderly, those in public housing, people facing mental health challenges, younger renters and new immigrants. They may lack the wherewithal to strong-arm their landlords into proper treatment; even if their landlords foot the bill for extermination, the potential costs of buying new furniture may be prohibitive; or they may try to hide the infestation from property management and neighbours alike, fearing blame or eviction. The same goes for public institutions, office settings and landlords themselves, who all too often attempt to hide the problem. Having dealt with my own secretive property manager, I am keenly aware of the disastrous repercussions of that kind of subterfuge. Yet I also begrudgingly understand the inclination toward silence. When confronted with bedbugs, even the most rational person can lose it.

As far as infestations go, I had one advantage: my new place was pretty much empty. That meant it was easier to access every crevice, plus I had no clutter to organize and few belongings to pull away from the baseboards. Propelled by terror, I scheduled a treatment as soon as the technician confirmed my infestation, refusing to wait for my building’s superintendent to act. Because of his sluggish response to my initial call and his attempt to hide the previous infestation, never mind his shoddy treatment of it, I didn’t trust him. But I also felt trapped and desperate for some control. I was now knowingly moving into a place with bedbugs. I had nowhere else to go, my movers were booked and I couldn’t afford to break my lease. If I’d been thinking straight, I might have gone to the Landlord and Tenant Board to fight for my first and last month’s rent back, but anxiety had overtaken my decision-making. So I paid more than $1,000 to treat my place and, because I felt guilty, to inspect my friend’s apartment, where I’d visited the day before I noticed the bugs. (Luckily, he didn’t have them.)

I didn’t want to risk spreading bedbugs to my old place and the furniture there—or anywhere else—so I forced myself to stay at my new apartment. Every night, I slept fitfully and anxiously, if at all. And every morning, I scanned for new bumps on my back, taking photographs to compare the bugs’ progressive feast. After a few days of this routine, the skin under my eyes turned aubergine with exhaustion. I was beyond relieved when the pest-control company treated my place later that week. The treatment included spraying a protective layer of chemicals around my baseboards and pipes that would kill the bedbugs as they emerged from their hiding places to feed. I dreaded moving my belongings from my old place into the new one—it seemed woefully stupid to bring bedbug-free furniture into an apartment rife with them—but I had no other option. I had to cross my fingers and hope the bug massacre I’d paid for would be the end of it. (It’s worth mentioning that I did none of this stoically. I cried a lot.)

The same day I moved my stuff in, the technicians returned for a second round. They also wanted to check that I didn’t have any traces of bedbugs on my furniture, which would indicate that I’d brought the bugs with me. (I didn’t.) This time, they sprayed the chemicals along the bottoms of my furniture and boxes. After the treatment, my place smelled rank but reassuring. The technicians calmly answered my repeated questions about how long it would take for the bedbugs to be gone. Though there was no guarantee I wouldn’t need another treatment—we couldn’t, after all, tell where they’d come from—I at least had a three-month warranty. I felt like I’d made the right decision, especially since my building’s super hadn’t called me back until after my first treatment. Even then, it was only to drop off sticky bug traps to supposedly confirm that I did, in fact, have bedbugs.

For the next few weeks, I’d wake up every morning to find my floors littered with dead, or dying, bedbugs. They were intent on swarming me, but the chemicals kept them at bay. My anxiety didn’t subside until months after I stopped sweeping up little carcasses every morning, and it never fully disappeared. In part, I remained convinced—correctly or not—that the units surrounding mine were infested. The pest-control company suggested that the building hire somebody to inspect and treat them, but the property manager dismissed it as a cash grab. They also heavily implied that I was responsible for bringing in the bedbugs and argued that, even if I weren’t, they shouldn’t have to reimburse me for the treatment since I’d gone rogue. After I wondered aloud whether I should divulge the infestation to my neighbours, they made it clear that my chances of getting any money back would greatly diminish if I did. To his credit, the super eventually went to bat for me against his boss, and after two months of haggling, I received a cheque for the full amount of my treatment.

A few months later, I developed a rash on my leg and insisted on paying a couple hundred bucks for another inspection that my pest-control company told me I didn’t need—and indeed, their visit confirmed the bedbugs hadn’t returned. I still moved as soon as I could afford it, eschewing rent control for the illusion of safety that a new building brought. And I still retain a high level of vigilance that I sometimes grimly joke about but know isn’t ha-ha funny. I won’t sit on public transit, no matter how long the ride, and will never set any piece of luggage on any bed. I routinely check my baseboards, my bed frame, my mattress, my bags. I scope out every public seat and often run a credit card through the seams of my furniture just in case. While reporting this story, I imagined enough bugs crawling on me to warrant stripping off my clothes immediately after I arrived home and stuffing everything into the dryer on high heat—twice. It’s all so ridiculous and excessive, and what’s worse, it may not even work.

****

Article by Lauren Mckeon for Toronto Life