The Breach: Airbnb has eluded regulation for years—now some housing advocates are demanding a ban

Posted September 7, 2022

Lauren Seward-Munday is being demovicted from the Ottawa apartment she and her partner have called home for the past 12 years. They’ve lived there since college and are now raising their child there.

Similar to a renoviction—the eviction of tenants to renovate and relist a property typically at a higher rate—a demoviction is the forced eviction of a tenant to tear down the property and rebuild.

Seward-Munday suspects the units will be listed on Airbnb once the rebuild is complete, since her landlord has rented out the two townhouses beside her on the online marketing website for the last three years.

The stress of losing her home is affecting her health, she said.

“I’ve been unable to eat at times and I actually ended up going to the hospital so I could have medication,” she told The Breach in a phone interview. “I worry because I have a 10-year-old son [and] my partner has disabilities, and I’ve been working from home during the pandemic.”

Seward-Murphy said the apartment isn’t just a place to live—it’s her family’s first and only home.

“This is where I brought my son home from the hospital,” she said. “This is everything I need to survive—it’s scary.”

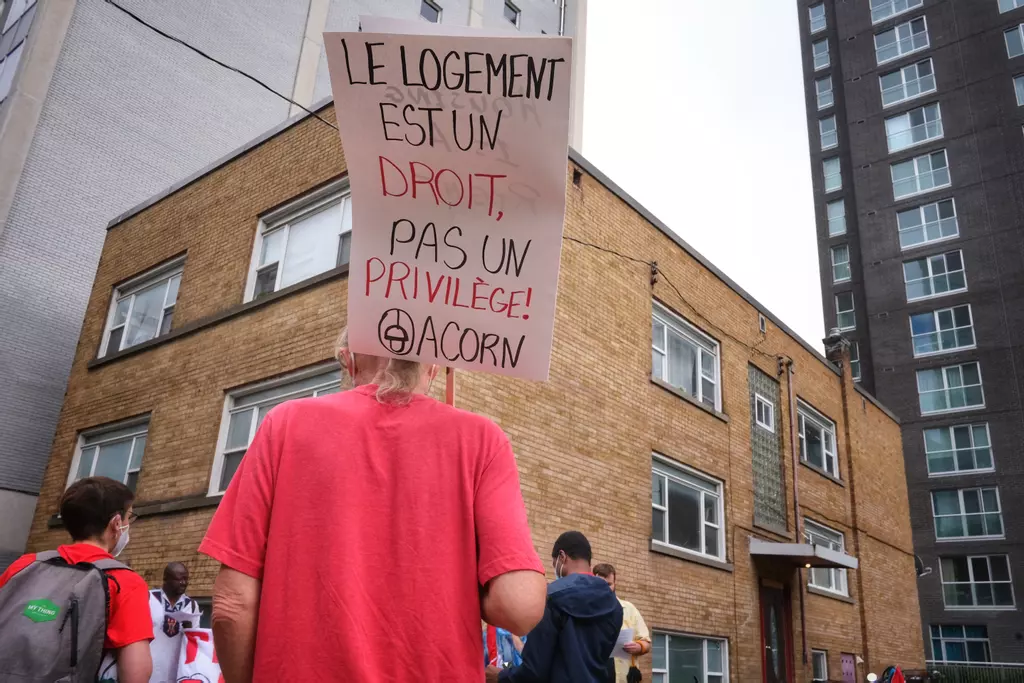

A board member with the Vanier Association of Community Organization for Reform Now (ACORN), a membership-based community union of low to moderate-income people, Seward-Munday knows well the difficulties other Ottawans face in accessing and maintaining long-term affordable housing.

She said she’s been priced out of Ottawa’s housing market—and with rent steadily increasing, she’s also been priced out of her neighbourhood, just east of downtown. “I just want a decent home for my family. I don’t want to do financial tetris to hopefully find something that works.”

The transfer of housing from long-term rentals to the short-term market can be lucrative for property owners, with peer-to-peer short-term rental platforms like Airbnb offering a streamlined process. But tenants are left vulnerable. They often face evictions and are forced back into a rental market with higher costs and diminishing affordable housing, due in part to the very platforms that are incentivizing property owners to convert their long-term rentals into short-term ones.

Across the country, governments have been scrambling to regulate Airbnb in an effort to protect rental housing. But those efforts are failing people like Seward-Munday and her family. Now, some are asking: can further regulation of Airbnb work? Or should the global rental platform be banned altogether?

How Airbnb takes short-term rentals off the market

Launched in 2008, AirBnB began as a way for people to share their homes and apartments and supplement their income. 14 years later, it is a major industry for real estate owners, who increasingly rent entire properties on the site to increase their income.

David Wachsmuth, a Canada Research Chair in Urban Governance at McGill University who studies the impacts of Airbnb, said that in major cities there’s a direct correlation between rising rents and the movement of long-term housing to the short-term rental market. “The more commercial Airbnbs there are, the higher the rent is.”

The platform’s surge in popularity contributed to the loss of approximately 14,000 homes from the long-term rental market in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver, a 2019 study conducted by Wachsmuth concluded. The same report estimated that more than 31,000 homes were being rented on Airbnb in 2018.

Today’s numbers are virtually unknowable, Wachsmuth told The Breach, because landlords are taking their rentals underground to avoid regulations looking to curb Airbnb usage.

According to Inside Airbnb, a website that publishes data on Airbnb’s impact on residential communities, more than 4,200 of the “recent and frequently rented” Airbnb listings in Montreal and Vancouver are entire homes and apartments—not just a room or unit in the homeowner’s residence.

In these cities, landlords can double or even triple their monthly revenues by moving their properties to the short-term market. At $150, Montreal had the fourth highest average nightly short-term rental price in 2021. With the city’s average rent sitting at around $1,517 a month, a landlord could achieve the same revenue on Airbnb in less than 11 days.

Sherwin Flight, who lives in St. John’s and runs the Facebook group Newfoundland Tenant & Landlord Support Group, has witnessed tenants’ desperate struggles to find affordable long-term housing in his province, where he said low-income tenants are being priced out of the rental market.

Some landlords are finding it more profitable to rent on Airbnb, he said, citing a recent long-term rental listing that advertised a three-bedroom unit but with one of the rooms listed at $223 per night. “If you can keep that booked for 30 days, it’s $6,690 before Airbnb takes its [three per cent] cut,” Flight explained. “That’s a similar income a landlord would get from renting a room to a tenant for six to eight months or longer.”

Wachsmuth said Canada’s total collective revenue of short-term rentals listed on all platforms—not just Airbnb—was around $2.1-billion in 2021. The top four destinations were Whistler ($89 million), Toronto ($80 million), Muskoka, Ontario ($75 million), and Montreal ($68 million).

Inflation and the dramatically rising cost of living has also added to Canada’s housing crisis. At nearly $2,000, the average cost for a one-bedroom unfurnished unit in the Greater Toronto Area has increased nearly $300 in just the past 12 months. Meanwhile, Montreal’s average monthly rental for one-bedroom apartments jumped $75 over the past month alone, now costing $1,539.

Not just an urban problem

Wachsmuth’s 2019 study found the number of active listings, total revenue, hosts with multiple listings, and frequently rented entire-home listings are all growing at substantially higher rates in small towns and rural areas.

On Vancouver Island’s west coast, Tla-o-qui-aht hereditary chiefs say members of their First Nation have been unable to return to their homelands due to the high cost of living; they’re asking for regional leaders to help address the problem. “The issue of affordable housing in Tofino and the surrounding area has intensified significantly over the past decade,” they say in a July 4 statement.

Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation Natural Resources Manager Saya Masso said while Tofino has long drawn tourists to the area, the cost of living has been driven even higher by the surge of short-term rentals. He estimates there could be as many as 300 or 400 Airbnb listings in the region, which has a population of just over 2,200.

“That’s a lot of people who would be residents, who aren’t anymore,” Masso said, adding the lack of affordable housing has forced many to live in tents.

Many regulations, little enforcement

Across the country, cities are regulating Airbnb and requiring property owners to register short-term rentals. Some are also collecting municipal taxes. But many property owners are taking their business underground, and municipalities are largely powerless when it comes to enforcement. According to Inside Airbnb, for example, more than 86 per cent of “recently and frequently booked” listings on the island of Montreal—approximately 2,415 units—are unlicensed.

In 2015, Quebec became the first province to regulate Airbnb, requiring hosts to register with Revenue Quebec. The province also charges hosts a $50-$75 fee for a registration number that must be posted at their rental properties. While Revenue Quebec issued more than 1,000 fines for infractions between 2019 and 2021, the agency can’t keep up with the estimated 100,000 listings province-wide. In 2023, a new regulation comes into effect that will actually make it harder to ban or regulate Airbnb rentals at the municipal level.

Wachsmuth said targeting Airbnb hosts directly isn’t enough, and that the company has a role to play. “Provincial rules, in my opinion, should require Airbnb to enforce the need for registration,” he said, pointing to Vancouver as an example. “You can’t find a listing on Airbnb if it doesn’t have a registration number, because Airbnb will not allow that listing to be posted because they made that deal with the City of Vancouver.”

In Vancouver, hosts are limited to a single licence and must include their registration numbers in all listings and advertising. This fall, Vancouver city councillors will vote whether to take the city’s regulations further by requiring short-term rental hosts to live on-site. It would be one of the most stringent short-term rental regulations in the country.

Smaller cities are following suit. In June, London, Ontario’s city council approved new regulations requiring premises to pass inspections, and for hosts to pay a 4 per cent municipal tax. Hosts can also now only rent out their primary residence.

In 2020, Calgary and Saskatoon introduced mandatory licensing. Ottawa followed suit this year and, like London, only permits Airbnb hosts to rent out their primary residences. Winnipeg is also looking into regulating short-term rentals.

In April, Nova Scotia announced it will soon also require hosts to register short-term rentals. This follows other provinces who have already regulated Airbnb, including British Columbia – which requires all hosts in the province to either acquire a business licence or permit. Those without are blocked from listing on Airbnb. Newfoundland also plans to impose regulations this fall.

Lobbying for a lighter touch

In a 2017 submission, Airbnb asked the federal Liberals to apply, if anything, “a light regulatory touch to help support those who are engaging in amateur home sharing activity to help earn extra income.” The company claimed that through the “democratization of capitalism” Airbnb is “empowering people and helping them combat wage stagnation and worsening economic inequality.”

Since 2019, Airbnb hosts have been required to pay taxes. Hosts that accumulate more than $30,000 a year through Airbnb must register and collect both Goods and Services Tax (GST), and Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) and/or the Quebec Sales Tax (QST) on what they earn. Last year, the federal government took this even further—requiring all short-term rental hosts providing accommodation through a digital platform to pay GST and HST.

Hosts with unregistered listings won’t be required to pay GST, HST and/or QST, but as a result of federal regulations Airbnb will be obliged to do so on the hosts’ behalf.

But Wachsmuth said there’s a gap between Airbnb and other sectors of the economy. “The simplest way to deal with this is if Airbnb has a responsibility to report income earned on its platform per person to the government the same way any employer does,” he said.

Should Airbnb be banned?

Catherine Lussier, an organizer with Quebec housing rights group Le Front d’action populaire en réaménagement urbain (FRAPRU), said regulating Airbnb isn’t working. Quebec’s provincial regulations have “proved ineffective in stopping the phenomenon.”

Montreal’s bylaws prohibiting short-term Airbnb rentals in certain neighbourhoods have also failed as illegal listings continue to occur in these areas, she added. This occurs as a result of lack of inspectors to hold illegal Airbnbs accountable and little follow-up when residents make complaints considering garbage and noise.

In 2018, Revenu Quebec—which monitors Airbnb regulations in the province—announced a team of 25 inspectors to hold illegal Airbnbs accountable and ensure hosts are complying with tax requirements. The Coalition of Housing Committees and Tenants Associations of Quebec (RCLALQ) said the number of inspectors does not meet current demand.

Their conclusion: Airbnb must be banned.

“Having more inspectors would make a dent in this illegal system of short-term rental. But how many inspectors do we need to control 100,000 listings,” asked Martin Blanchard, spokesperson for the RCLALQ. There will never be enough inspectors to impose a real deterrent on illegal short-term renting, Blanchard said.

“They are more powerful than a handful of inspectors.”

“The best way to stop [these issues] is to prohibit any usage of these types of platforms,” said Lussier. She said homes and apartments should be prioritised for residents, while tourists should continue to access hotels and hostels.

Wachsmuth sympathizes with housing right advocates calling for a ban on Airbnb. “They’re correctly observing that the good faith attempts by cities to find a balance has been thwarted by all of the Airbnb hosts who are breaking the law and by Airbnb failing to be a cooperative partner,” he said.

But he believes stronger regulations could limit sharing to spare rooms and times that primary residents are away. “I’ve always felt, personally, that home-sharing is a really great idea and represents a potential win-win for cities,” he said.

“If I’m out of town for a weekend or a week in the summer, the idea is that instead of my house just sitting empty, someone can stay in it.”

A community-owned platform?

Could Airbnb be replaced by a more socially conscious platform? A Toronto-based group that pushed for short-term rentals to be regulated launched Fairbnb. It’s a short-term rental platform that uses the same technology as Airbnb, but half of the booking fee are donated to community projects—in Toronto’s case, the Kensington Market Community Land Trust. The creators promise that no long-term affordable housing will be removed from the market, as Fairbnb abides by Toronto’s rules—requiring that hosts only rent out of their primary residence.

Lussier said Fairbnb is less problematic than Airbnb, but questions what methods are in place to verify hosts are only booking their principal residence. “One of the problems with the Airbnb platform is that there is not a real verification,” said Lussier, questioning if it’s the hosts sole residence or if they own multiple properties.

Too late for the renovicted

Despite efforts from all levels of government, rents are still rising, entire homes are being rented on Airbnb in some locations, and as a result tenants are still struggling to find long-term affordable housing. Many are still asking for their provincial government to impose more regulations to save long-term housing.

“Nothing that the government had put in place really worked for stopping the phenomenon and protecting tenants that [experience] the consequences of the amount of Airbnbs in their neighbourhoods,” said Lussier.

Lussier said some cannot afford living in their neighbourhood anymore as a result of Airbnb causing rents to rise. She said, “With the pandemic, it has been slowed, but the amount is still really high.”

Seward-Munday said while some municipalities are getting to work regulating Airbnb, it’s too little, too late for her. “I feel like they need to work on things at the provincial and federal levels as well, in terms of helping the financialization of housing so people can actually have a place to live.”

***

Article by Savanna Craig for The Breach