The Globe & Mail: Opinion: Don’t bank on a fully cashless society

Posted November 8, 2021

Posted November 8, 2021

Casey Plett is the Scotiabank Giller Prize-nominated author of A Dream of a Woman.

When I worked at the Strand, New York’s biggest bookstore, our internet would often go down, making things very inconvenient. After all, a lost connection meant that the credit card machines ceased to work. “We can take cash!” I and other cashiers would holler at our long lines of customers, but only a trickle out of the book-loving hordes would actually take us up on the offer. The rest would either leave, or wait – sometimes for a very long time – for the machines to come back online.

It’s common to believe we’re becoming a “cashless society.” Such observations tend to regard this as a fait accompli – as if currency were simply one of so many Old World analog relics circling the drain before they gurgle into oblivion – and an inevitability accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In those early days in which we simply didn’t know about whether we could catch COVID-19 through objects touched by infected people, many institutions phased cash out entirely to reduce physical contact between customers and staff. Those concerns are no longer founded in scientific evidence; there is plenty of research to show that the virus is airborne and spreads through sharing air, not countertops, and we’ve known this for a while now. And yet businesses have largely not pivoted back – and if anything, more businesses are focusing on non-cash transactions.

But a cashless society is not a foregone conclusion. And while it may seem like a fuddy-duddy Luddite concern – the equivalent of clinging to one’s touch-tone phone, perhaps, or making a plea for beepers – a complete societal changeover to non-cash payment would not, in fact, be a good thing.

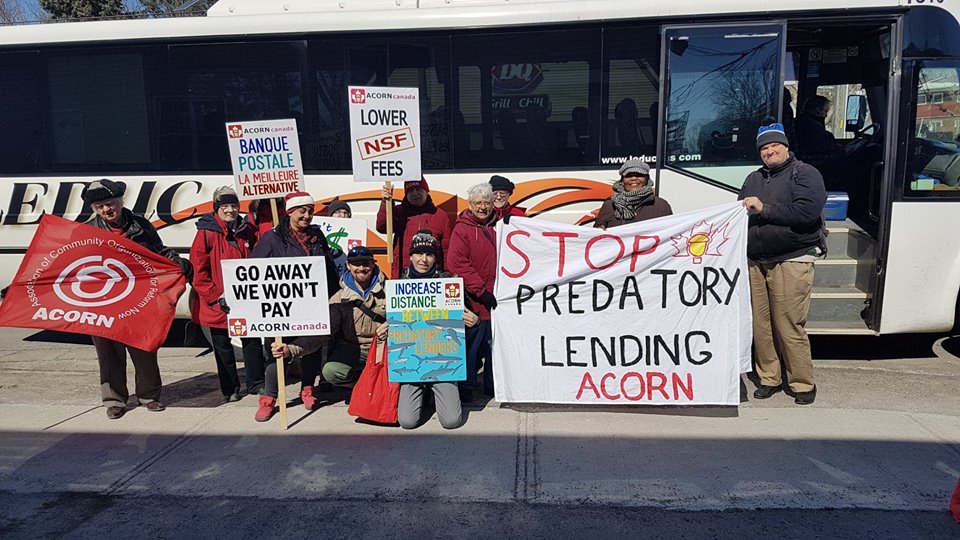

A fully cashless society would be inequitable and undependable, because not everyone has access to the banking system. Vulnerable and homeless people, as well as many who are sex workers, lack proper ID or are undocumented, and thus lack the ability to open an account. “In an increasingly cashless economy, the banking industry exerts a terrifying degree of control over us all,” Charlotte Shane noted in The Cut when OnlyFans announced it would ban the sexual content that brought the platform riches, shortly before reversing the decision. Banking accessibility is an issue that affects a lot of us. According to a 2016 report by Acorn Canada and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, one million Canadians are unbanked, and an additional five million are underbanked – that is, people who have a bank account but no credit, people who are unable to afford fees or high-interest rates linked to products for low-income borrowers, or those who live in a neighbourhood that does not have a bank branch.

In other words, many who depend on cash are already socially and economically marginalized; permanently phasing out cash would only marginalize them further. Indeed, when a retail institution decides to go cashless, ask yourself: Who’s being told to leave? Who’s being told they don’t matter?

Further, everyone needs a failsafe. What if the internet goes down, and you’re out in the country without reception? Your card is locked for reasons you cannot comprehend, and while you fight with the bank to figure out what’s going on, you still need to buy food and gas and toilet paper. What’s your next option? Sometimes the stakes are higher than missing out on books at the Strand.

Despite owning credit cards, I always have cash on me, for the same reason I keep a road atlas in my car despite the omnipresent chirp of Google Maps. True, I probably won’t need that atlas, but I know I’m definitely screwed without it if I do. A fully cashless society would only increase our reliance on systems that have never proven themselves 100-per-cent reliable.

And then there’s the question of privacy. When my father turned 40, around the turn of the millennium, he wryly noted that his Yahoo! e-mail account began showing ads for Viagra. At the time, it seemed creepy. How innocent we were. It’s now widely accepted that tech companies track every piece of ourselves in order to micro-market and sell it back to us. Yet does anyone really want to further give up such a refuge of privacy? The Globe and Mail echoed this in 2019 too: “Whenever personal data are amassed, there is the risk of the data being abused or falling into the wrong hands. And when it comes to payments, there’s really only one way to avoid that.” And that is by using cash. (The American Civil Liberties Union agrees, by the way.)

Removing cash as an option hurts businesses, too. There are hidden costs to all our swiping and tapping: The fees that credit card companies take from businesses range from 1.3 per cent to 3.4 per cent of every transaction. Any small business running on tiny margins – that is, most of them – will tell you that adds up, benefiting larger chains or companies that have more ability to tolerate these costs. These costs are usually hidden to the consumer, but they are passed along. Literally everyone loses – except the card companies and payment processors, naturally.

Some governments have taken action to push back in the name of cash. Massachusetts has mandated that the state’s businesses take cash since 1978, while Colorado and Washington, D.C., have passed similar laws within the last year. And New York barred businesses from refusing cash last year, following in the footsteps of Philadelphia and San Francisco. “I have constituents who have no access to debit or credit and even if you do, there are some constituents, particularly the elderly, who prefer cash,” Ritchie Torres, the then-city councillor who was the lead sponsor of the New York legislation, told CBS. “The choice should belong to the consumer.”

But there are no Canadian jurisdictions that require that businesses do the same. “No law requires anyone to accept bank notes or any other form of payment to settle a commercial transaction,” a Bank of Canada spokesperson told Global News last year. The central bank did, however, issue a notice to businesses asking them to continue to accept cash, even during the pandemic.

I know firsthand that there are plenty of reasons for retail workers to not love cash. Opening up and closing down a till takes exponentially longer with a cash drawer. The runs to the bank are a pain. It’s safer for businesses, too, as it reduces one avenue for theft.

Still, the alternative would be to deny basic rights to the homeless and unbanked. That doesn’t justify removing fail-safes for when there are technology troubles, and clearing yet another road for privacy violations, all at an increased cost. Not unlike the printed books that continue to sell at Strand, some old inventions survive for good reason. Cash doesn’t have to be king, but it still needs to be on the board.

***

Source: The Globe & Mail