The Globe and Mail: Lenders are about to face a cap on interest rate charges. Now consumer advocates worry they’ll push optional insurance products

Posted December 24, 2024

The maximum interest rate that creditors can legally charge is set to drop in the new year, but consumer affairs experts and advocates are now urging Ottawa to expand the kinds of borrowing costs covered by the cap, warning the lower limit will likely spur high-cost lenders to turn to ancillary charges.

Ottawa has set the criminal rate of interest at an annual percentage rate (APR) of 35 per cent, down from the current ceiling of roughly 48 per cent, a measure billed as a crackdown on high-interest lending such as pricey instalment loans from alternative lenders. The change will apply to new loans starting Jan. 1.

But in its 2024 budget, the federal government said it was also considering including the cost of optional insurance products on high-cost credit in the new cap, an announcement broadly seen as targeting pricey creditor protection insurance. Such products help borrowers and their families pay off debt in case of job loss, disability, critical illness or death. In August, Ottawa published details of the proposals in draft amendments.

Some experts and anti-poverty groups say expanding the cap to insurance charges is necessary because of the risk that lenders will step up their efforts to sell creditor protection insurance, on which they often earn a commission, as the new interest rate limit puts pressure on the industry’s profit margins.

“One concern is, with the lower interest rate cap, will lenders push credit insurance even more because it’s a profit centre for them,” said Gail Henderson, a law professor at Queen’s University.

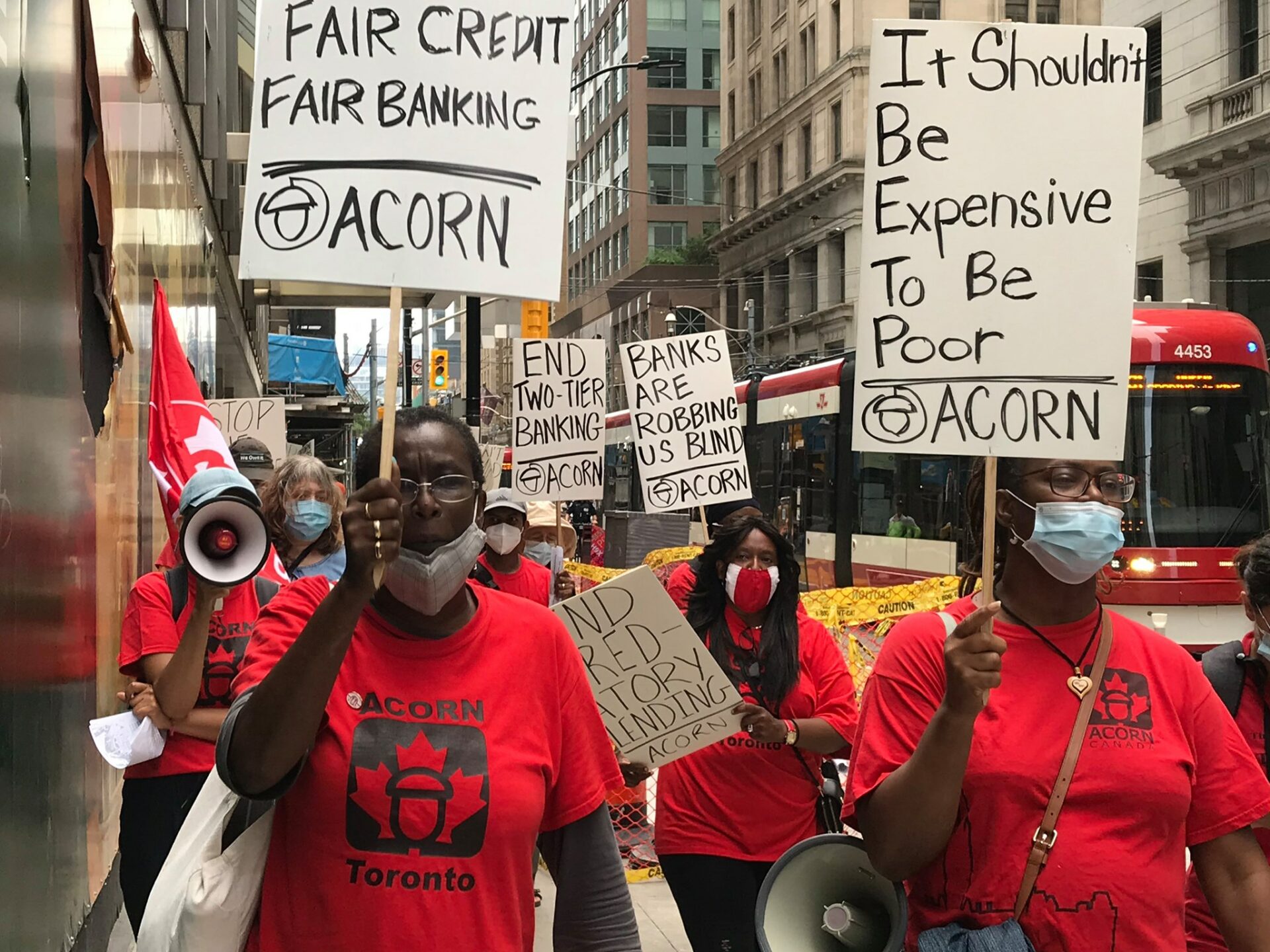

Organizations such as Acorn Canada, which advocates for low- and moderate-income people and championed the lowering of the criminal interest rate, have also long asked Ottawa to include creditor insurance in the overall cap.

The Canadian Lenders Association (CLA), on the other hand, has said the change will likely prevent the industry from offering optional default insurance to an estimated 3.6 million high-risk borrowers.

“Millions of Canadians are going to lose the right and the access to buy an optional insurance product that provides them meaningful financial protection and financial peace of mind in the event they run into death, disability or job loss,” said Jason Mullins, the CEO of non-prime lender Goeasy, who spoke to The Globe and Mail in his capacity as the vice-chair of the CLA, which represents banks and instalment lenders but not payday-loan providers.

The CLA estimates that hundreds of millions of dollars in creditor protection insurance payouts helped borrowers keep up with debt payments when unemployment spiked across Canada in the early stages of the pandemic, Mr. Mullins said.

Other industry groups have criticized the idea of an expanded rate cap that would lump insurance with interest-related charges.

The Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association said in a submission to the Department of Finance that it is concerned that the broad definition of insurance in the current proposals could capture a variety of products, including mortgage, property and auto insurance.

In general, there are also longstanding questions about whether the criminal rate of interest is enough or the best way to regulate the high-cost credit market.

Making it easier for borrowers to declare bankruptcy, for example, could incentivize lenders to better assess the debt burden their clients are actually able to carry, said Stephanie Ben-Ishai, a law professor at York University’s Osgoode Hall Law School.

The minimum cost of filing for bankruptcy is currently around $2,000, a prohibitive amount for many low-income borrowers, she added.

Still, given that Canada does have a cap on interest rates, it makes sense for Ottawa to include credit insurance charges, Prof. Ben-Ishai said.

Advocates of the measure point to concerns that the optional coverage is often mis-sold. Canada’s federal financial consumer watchdog has repeatedly flagged misleading sales of such products. But provisions recently added to the Bank Act should limit such sales practices at those institutions, Prof. Henderson said.

Still, those rules don’t apply to high-cost lenders that are provincially regulated.

“The greater concern is the alternative lenders and people who are shut out of the prime lending market who have limited options and maybe are desperate for that money,” she said.

A 2022 survey conducted by Acorn found that nearly 30 per cent of its members with high-cost loans said they had taken out the loans without realizing they would have to pay insurance charges or that the lenders suggested they sign up for coverage without explaining the product. Another 4 per cent reported being told that signing up for creditor protection was mandatory.

And creditor insurance can saddle high-risk borrowers with steep costs. B.C.’s consumer protection watchdog, for example, warns that the cost of optional products such as loan insurance can end up costing debtors more than the amount they borrowed.

Article by ERICA ALINI for The Globe and MailThe Globe and Mail