CBC News: A telecom giant’s secret world of low-income housing

Posted May 6, 2021

Posted May 6, 2021

Every few weeks or so, uniformed bailiffs working hand-in-hand with a Toronto-based collection agency treaded up and down the stairs of a series of low- and mid-rise apartment buildings in a handful of the Halifax region’s poorer neighbourhoods.

Often they traipsed down narrow hallways, knocking on doors to serve renters, many living on the financial fringes, with eviction or tenancy board notices. Sometimes they called ahead to organize a spot to meet. As many as 50 forms a month were handed out.

The tenants were all behind on their rent. A single snapshot, from August 2019, showed some owing as little as $291, others nearly $2,000, according to court records. Among them were those on social assistance, including a single mother of a toddler who said she had nowhere else to live.

Some managed to pay and stayed, some simply left. Others were evicted, their rental debts to become a potential financial yoke for years to come.

It was all business as usual.

What many of the tenants likely didn’t know, however, was that efforts to chase them for back rent or force them from their homes were ultimately being done on behalf of entities on the other side of the country: a corporation led by a Calgary real estate mogul, and the pension plans of a Canadian telecommunications giant.

It is a chasm, both financial and geographic, between evictees and the behind-the-scenes corporate owners of the buildings that has become a creeping reality across tracts of low-income housing in the Halifax-area communities of north- and east-end Dartmouth, and parts of Spryfield.

As the city grapples with what many say is an affordable-housing crisis, CBC has sought to analyze the ownership webs behind certain property portfolios, and examine the business side of those rental operations and its implications for residents.

They are multi-unit clusters collected through bankruptcies and big-money deals, and they are run with a sometimes hard-edged approach: the push for profits trickling down into a machinery that will pursue tenants for even modest amounts of overdue rent, often under threat of eviction.

Among the tenants captured in the 2019 court records were a number that lived in a string of well-worn, cheap-rent apartment buildings that date to the 1970s along what’s known locally as the “500 block” of Herring Cove Road, on the edge of Spryfield.

It’s a stretch that’s been the source of a number of tenant complaints to the city. Last August, a bug infestation became so bad a pest-control company was scheduled to do what municipal records called a “whole building cleanout.”

In February, a number of residents held a rally to protest what they said was poor maintenance. It apparently spurred building management to take some action: repairs to a laundry room floor and a tenant’s bathroom followed, and common areas have been cleaned more often.

Still, on a recent day, garbage, abandoned furniture and an upturned bin of clothes lay scattered beside dumpsters in the parking lot behind five buildings. More trash was strewn down an embankment and into some adjacent woods.

“This is ridiculous,” Darlene Cooper, who has lived in a unit at 536 Herring Cove Rd. for six years, said in exasperation.

Along a driveway bordered by mud from the day’s rain, Jean MacDonald, a mother who lives with her six children in a three-bedroom unit, sat in her vehicle, her youngest son sleeping in the back.

Along a driveway bordered by mud from the day’s rain, Jean MacDonald, a mother who lives with her six children in a three-bedroom unit, sat in her vehicle, her youngest son sleeping in the back.

She had recently been issued a formal warning under Nova Scotia’s Residential Tenancies Act that serves as a first step toward evicting a tenant for unpaid rent.

It said she owed $100. If she didn’t pay, the notice said, she could be out in 18 days.

Her rent had increased slightly in December to $876 a month, but MacDonald said she had refused to pay the difference since then due to a cockroach problem in her unit. They had infiltrated her stove, her shelves, even her daughter’s toy box.

Not long after the rental-arrears notice, she was issued a fresh one: it told her to remove “any clutter and fire hazards and clean your suite,” suggesting it was leading to the pest problem. If she didn’t, it warned, she could be evicted.

“Where am I supposed to go? There’s nowhere,” MacDonald said. “I don’t want to be homeless with six kids out on the streets.”

Five of the six apartment buildings along this stretch of the 500 block are run by Toronto-headquartered Metcap Living Management Inc., a property management firm that operates thousands of multi-family units in five provinces.

It is not, however, the owner — and tenants would be hard-pressed to find out who is. Even property records are cryptic, listing the ownership as 9741631 Canada Inc.

It turns out the numbered company is the creation of the pension investment arm of Telus Corp. And it owns more than 45 apartment buildings in Nova Scotia, largely in the Halifax region.

In short, the 500 block is an investment vehicle. Each apartment unit, MacDonald’s included, is a tiny revenue stream that helps pay for the retirement of employees of the country’s second-largest telecom.

“I’m kind of floored with that information,” MacDonald said, when told of the Telus connection. “And they’re going to let us live like this? Like, how do you sleep at night?”

Getting a broad picture of evictions in Nova Scotia is difficult. While the provincial government knows how many orders are issued each year through its residential tenancies program, a spokesperson said it does not track for what reasons the orders are issued, such as rental arrears, damages to property or disputes over security deposits. The program also does not tabulate evictions, and the government said it is policy not to release data about particular landlords.

But an analysis of records compiled for CBC by the Nova Scotia Courts shows that between 2015 and 2019, more than 550 residential tenancy orders were filed in court against renters living in 1,200 apartment units run by Metcap, three-quarters of them currently owned by Telus.

That is double what is listed during that same period for Killam, the Halifax-headquartered real estate investment trust that operates nearly 6,000 units in the province and is the largest apartment building operator in the Atlantic region. The Metcap numbers are also higher than Capreit, another large residential building owner in Nova Scotia.

Not all tenancy orders are sent to small claims court. But doing so means it can be enforced. A sheriff can evict a tenant who refuses to leave, for instance, and their rental debt can be logged on their credit rating, a measure that can hobble them for years if they are unable to pay — and hurt their chances of finding a new place to live.

All this has taken place while the rental market in the Halifax area has turned red hot. Vacancy rates began dropping in 2016 and have hit record lows in recent years, while average rents have risen by 20 per cent during the same period. There is no shortage of desperate renters to fill newly freed-up units.

The Metcap-related data compiled by the Nova Scotia Courts does not describe the reason for each order, but those reviewed by CBC suggest they often involve ordering a tenant to vacate their unit and pay what rent is owed. Metcap CEO Brent Merrill told CBC the company typically only obtains orders against tenants for unpaid rent.

He said in an email, however, that the court numbers “do not match our records,” and that “many residents fulfill an order by simply paying their arrears.” He would not release Metcap’s in-house eviction statistics.

“Metcap follows the procedures set out by the Nova Scotia government in collecting rents from its residents,” he said in the email. “We do work with any resident struggling to pay rent in the COVID era helping them where necessary with payment plans to assist them in meeting their obligations.”

“Metcap follows the procedures set out by the Nova Scotia government in collecting rents from its residents,” he said in the email. “We do work with any resident struggling to pay rent in the COVID era helping them where necessary with payment plans to assist them in meeting their obligations.”

This type of dominance by large investors in certain neighbourhoods echoes across the country, from Toronto to Yellowknife. The last two decades have witnessed the dramatic rise of firms that have bought residential buildings en masse as investments.

One study, by University of Waterloo assistant professor Martine August, found that 17 of Canada’s 25 largest landlords in 2017 were real estate investment trusts or other types of asset management companies and equity firms. All told, they owned nearly 300,000 apartment suites.

August said those firms are driven by the financial motives of investors, and can squeeze higher profits from the properties with more sophistication: finding new ways to cut expenses, raising rents through renovations and tenant turnover, and charging extra fees for things like parking and storage.

“It’s not to say that you have a small-scale mom-and-pop landlord who’s inherently good and then a financial landlord who’s inherently bad,” she said in an interview.

“But what I’ve found in my research is that there does seem to be a qualitative difference between the way that these financial firms operate their buildings in ways that affect tenants on the ground, and in ways that are driving pattern affordability problems in our cities.”

The same investor push into apartment-building ownership is true in the Halifax area. A drive up Primrose Street in north-end Dartmouth takes you to what can easily be described as Metcap land. Company signs are staked into the ground or fixed to exterior walls, like an election campaign, albeit with a single candidate.

Metcap runs the buildings on behalf of a couple of large investors. The first is the Telus Pensions Master Trust, which was set up by the company for its pension plans. Last year, the fund took over full ownership of dozens of properties in Nova Scotia it had co-owned since 2015 with Strategic Atlantic, a subsidiary of a real estate enterprise led by Calgary businessman Riaz Mamdani. He had plucked the Halifax-area holdings out of the 2014 bankruptcy of a local property company.

Known as both a highly praised philanthropist and a polarizing figure who has faced multiple lawsuits and a massive receivership, Mamdani was shot by an unknown assailant in 2016 while driving his Rolls-Royce out of the driveway of his Calgary mansion. He survived.

Recently, a second major property owner entered Metcap’s Halifax-area management fold. Last year, Toronto-based Starlight Investments, which manages $20 billion in real estate and securities and is led by Daniel Drimmer, purchased Northview, a sprawling cross-Canada real estate investment trust that owned more than two dozen apartment buildings in Nova Scotia.

Telus’s vice-president of investment management, who is listed as president of 9741631 Canada Inc., did not reply to an interview request, and a Telus spokesperson referred comment for this story to Metcap.

Merrill, the CEO of Metcap, said in an email that the company has a “very strong maintenance program,” and there are cleaning staff in all “building clusters.” He said a customer service department is available by phone and email seven days a week, and units are inspected at least once a year for repairs and other issues.

As for Jean MacDonald, the 500 block tenant who faces potential eviction, Merrill said it will not pursue at a tenancy board hearing for an amount as small as $100.

Mamdani, through a spokesperson, declined an interview request.

“As a Canadian company, we are proud to own affordable residential rental properties in the Atlantic provinces and to participate in the local economy,” said a statement attributed to Mamdani, whose company still owns a dozen apartment buildings in the Halifax area.

“Our business strategy includes owning and investing in real estate for the long term, and we hope to be a part of the Nova Scotian community for years to come.”

Drimmer, Starlight’s CEO, did not reply to an interview request.

A key to Metcap’s rent collection operations in Nova Scotia has been a sister company based in Toronto called Suite Excel Collections Canada Inc., whose chief executive is listed in corporate records as Merrill, the head of Metcap.

Rick Doyle, a former mixed martial arts fighter and founder of Dartmouth-based Fivestar Bailiff & Civil Enforcement Services, worked for Metcap in 2018 and part of 2019. His company served hundreds of rental-arrears notices in the Halifax area and represented Metcap at residential tenancy hearings.

While effusive in his praise for local Metcap management — “nothing but beautiful people” — he said his relationship soured due to the influence of Suite Excel, which was deployed by Metcap to handle rental arrears.

“Our dealings with Suite Excel were not as good as the local relationship here. They were disrespectful to my staff, and ruthless in their pursuit of their objectives,” Doyle said in a recent interview.

That objective, he said, was to swiftly evict non-paying tenants, with no opportunity for compromise. He said his company, by contrast, had always sought to mediate between landlord and tenant and attempt to find a solution that worked for both.

His dealings with the company ended acrimoniously. After resigning his contract, Doyle successfully sued Suite Excel and Metcap for $10,878 in unpaid invoices.

He sees both sides. At one point in his life, he said, he hit “rock bottom” and wondered if he would be able to keep the roof over his head.

Still, bad tenants, Doyle said, can be a scourge on a building, intimidating or threatening other renters, playing loud music at all hours, punching walls or running drug-dealing operations out of their units.

Blame falls to the landlord, but it can take months to evict the person. It’s other tenants who suffer, he said. Many are low-wage earners who can’t afford to move anywhere else.

“It’s a very sad overall situation and it’s surprising how large of a percentage of our population is locked in this,” he said. “But if you saw what we saw on a daily basis, it’s a no-win scenario. It only takes one person in a building to cause absolute terror or mayhem.”

The issue is acknowledged by tenants as well. Pat Donovan, who helped organize the protest earlier this year at the 500 block, called Metcap “sly” in its handling of tenant issues, but added not all the problems should be put at its feet.

“To be fair to the company, some of the tenants are not so good either,” said Donovan, who lives in the building at 536 Herring Cove Rd. “You got tenants who beat things up, break things up, just don’t seem to care.”

Residential tenancy records filed in court reflect the difficulties on all sides. In some cases, tenants facing eviction appear to be able to string out appeals and stay in place for months without paying rent. Some have acted aggressively with property management staff.

Other cases are heartbreaking. One 51-year-old woman with a debilitating degenerative bone disease took in $1,100 a month in social assistance, including money meant to cover medical equipment. She was routinely short about $100 on her monthly rent of $640 for a one-bedroom unit on Primrose Street run at the time by Northview, and now owned by Starlight. A judge signed off on her eviction while her housing support worker said she was in hospital.

She is one of nearly 500 Northview and Starlight tenants who have been the subject of residential tenancy orders filed in small claims court in the last six years, according to Nova Scotia Courts data.

She is one of nearly 500 Northview and Starlight tenants who have been the subject of residential tenancy orders filed in small claims court in the last six years, according to Nova Scotia Courts data.

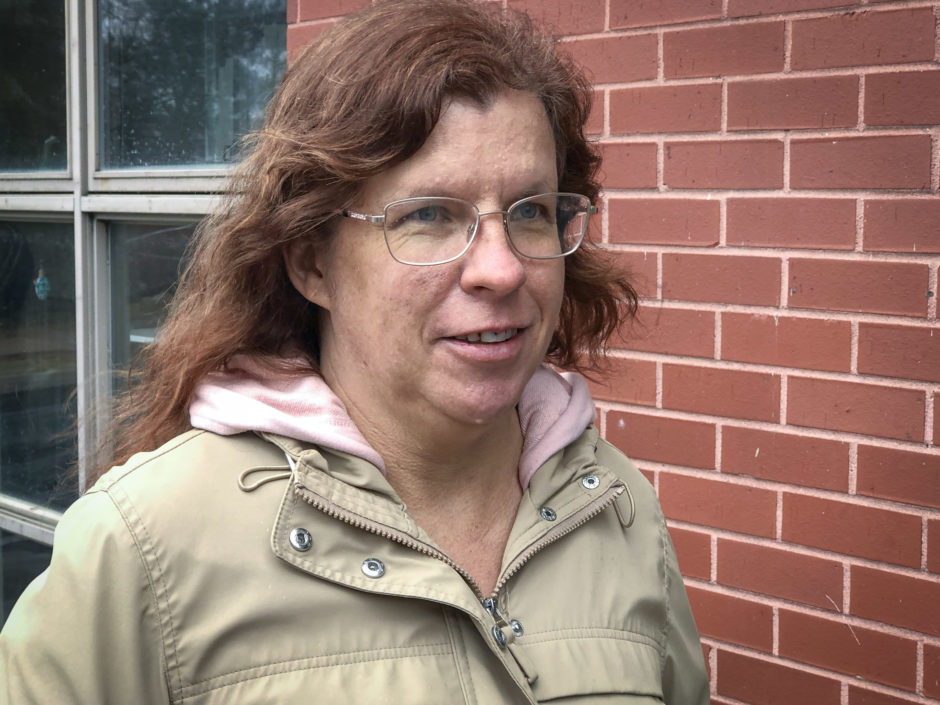

How landlords treat old rental arrears can have major implications for prospective tenants. Heather Rideout said she was evicted from a Metcap apartment in north-end Dartmouth for unpaid rent and ended up in a shelter.

“Nothing I’m proud of, but life gets to you sometimes,” she said.

She had other rental arrears in her past. It made it difficult to find a new place, especially in Halifax’s hyper-tight rental market. She finally got a room in a rundown building, and only recently found a better place on Quinpool Road in central Halifax. Her new landlord allowed her to move in on the condition she arrange for a trustee to manage her social assistance payments and ensure her $600 monthly rent was always paid on time.

Rideout’s story is hardly unique. Darcy Gillis, a housing support worker with the non-profit Welcome Housing who has extensive experience in north-end Dartmouth, said many of his clients have poor credit ratings, often due to old rental arrears, unpaid bills or payday loan debts.

“People just don’t make enough money to make the payments on them,” he said of the debts. “So they’re forever going to be in collections and their credit scores forever be taking that hit, because, you know, every dollar counts to them.”

With vacancy rates so low, large landlords are “not going to look at anyone with a poor credit rating,” he said. He doesn’t begrudge them, but notes it wasn’t always that way.

Metcap has in recent years played in an important role in the Halifax area’s affordable-housing world, providing units at prices many low-income people can afford. Provincial data that specifies Department of Community Services spending on direct rent payments to landlords suggests many Metcap residents are on social assistance.

Some tenants said in interviews they were satisfied with their accommodations, appreciative of the low rent and that their particular building was quiet with no disruptive tenants. A number of housing workers said they had descent relationships with the company, and worked with local management to iron out any problems raised by tenant or landlord.

Still, Gillis said he worries Metcap’s ascendancy in north-end Dartmouth has created an unhealthy monopoly. Metcap now controls a third of the rental market in the neighbourhood north of Victoria Road and Albro Lake Drive, which has the most apartment units of any census tract in the city.

Those who don’t want to rent from the company, or who can’t, have fewer options, he said. It’s also becoming more expensive. Metcap used to be a go-to when trying to find housing for clients. But rents on units that hit the market are rising, he said, putting them beyond many of the city’s poorest.

“My greatest fear is that a lot of people are going to continue to be pushed further and further outside their home communities,” he said.

Precisely how much profit the properties in Dartmouth and Spryfield are making isn’t clear. But there are hints. Mamdani noted in an Alberta court affidavit last year that the Strategic Atlantic properties in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were “collectively cash-flow positive.”

A spokesperson for the company said it would not share detailed financials, but noted the properties “have generated a modest profit; if they did not, they would likely not be a part of the company’s real estate portfolio today.”

Before it was sold, Northview was a public company and owned nearly 27,000 multi-family units across the country. In 2019, it paid out more than $96 million to investors.

Assessment values of apartment buildings in north-end Dartmouth also suggest that some of them have become increasingly profitable. Unlike single-family homes, the assessed value of many apartment buildings in Nova Scotia is derived from a formula that includes how much rent is taken in, and the expenses involved in running the building.

While some properties currently under Metcap management have only inched upwards, others have skyrocketed, including some that have doubled in value over the last 10 years, according to data from Viewpoint Realty. Recent sales in the area involving non-Metcap buildings suggest buyers are noting the potential for profits. One 12-unit building on Primrose Street sold last year for $884,188, three times its assessed value in 2012.

When apartment buildings sell for above assessed value, it suggests the buyer believes they can generate higher rents than what is currently charged, according to Giselle Kakamousias, vice-president of the property tax division for real estate consultant Turner Drake & Partners.

“For an example, let’s use a 10-unit apartment building and the rents are $800 a month. The purchaser may say to himself, ‘Gee, I think those rents are low, I think there’s a potential to increase those on rollover, or whatnot, maybe up to $1,000 a month,” Kakamousias said.

Those at Welcome Housing and Support Services in Halifax sometimes see clients who have only a few dollars to last them the month after their rent and power bills are paid.

Once a month, the tenants of landlords like Metcap rap on the door of Welcome Housing and Support Services, a non-profit on Gottingen Street in Halifax that manages money for more than 200 low-income clients, many on social assistance or receiving Old Age Security.

Inside, a printer in a small office spits out dozens of cheques. The amount on each is what is left over for the client at the end of the month after rent and power bills are paid.

Depending on circumstances, some cheques are for more than $600. Other amounts are so small — as little as $2 — they don’t even bother handing one out.

Sometimes a couple of bucks is all there is to cover groceries, the phone bill, clothes, and anything else for the next 30 or so days.

“When you’re standing at the door and you’re handing them that cheque and you see their mouth drop and their eyes open,” said Michelle Myra, a Welcome Housing worker. “So then you do everything you can.”

***

Article by Richard Cuthbertson for CBC News