CBC News: Hundreds of Nova Scotians are on hidden bad tenant lists on Facebook

Posted September 4, 2021

Posted September 4, 2021

Renters in Nova Scotia are facing a shortage of affordable homes amid stiff competition, often with children and pets in tow.

Renters in Nova Scotia are facing a shortage of affordable homes amid stiff competition, often with children and pets in tow.

But there might be another reason why an application gets turned down.

In various Facebook groups, some hidden and some public, landlords swap photos and names of tenants with whom they’ve had bad experiences. Advocates have flagged at least two ‘bad tenant’ lists with hundreds of names in such groups.

“A landlord could easily put something up there just for a sake of a petty vengeance,” said Fabian Donovan, a member of Nova Scotia ACORN, an organization that advocates for people with low to moderate incomes. Donovan is a renter in Halifax.

“And once it’s out there, it cannot be taken back.”

Such lists are concerning for advocates, legal experts and property owner associations. But some landlords say they’re forced to take matters into their own hands to protect themselves.

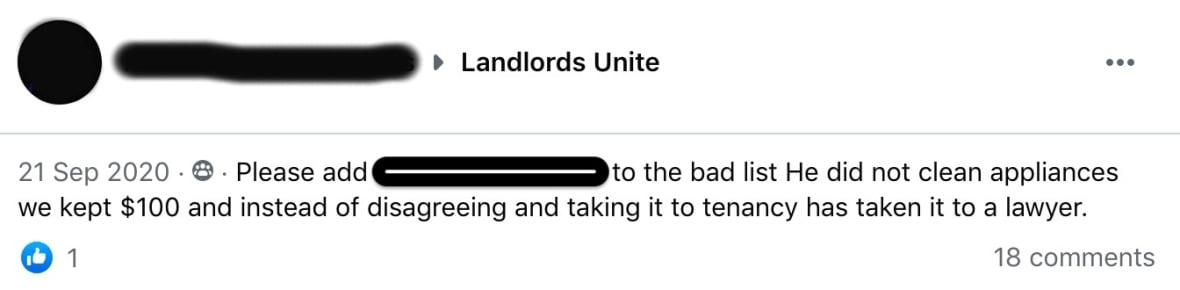

Earlier this month, N.S. ACORN launched a campaign highlighting screenshots of posts they’d gathered from the hidden “Landlords Unite” Facebook group over the past year and a half.

The Nova Scotia chapter said its membership in the Facebook group allowed them to see various files, including a “Do Not Rent” list that had 256 names as of Aug. 21.

They said names were added to this list for various reasons, including anti-landlord social media posts or replying rudely to rental listings.

Another list with nearly 3,200 names was compiled on a hidden Facebook group called “Amherst Landlord Associates,” ACORN said, including some names pulled from police records.

CBC News confirmed that at least the Landlords Unite list is still visible on the group as of this week. Some screenshot posts from ACORN also show landlords discussing offline lists they’ve created for regions around the province.

Another group called Landlords Nova Scotia, which is open, regularly shares photos and names of tenants who have allegedly not paid months of rent, or caused huge amounts of damage and left behind piles of garbage.

“Who knows what was going on. Maybe … the person had a bad marriage. They broke down and he couldn’t afford to pay the rent,” Donovan said, adding that people being named could have had mental-health episodes, or be one of many who lost work during COVID-19.

Donovan said he understands why landlords are upset when they lose out on rent or have to spend large amounts cleaning out their units, but there are legal ways to go about dealing with those situations. He said they could always go through the residential tenancy system, or a collection agency.

ACORN has said anyone who wants to know if they are on a bad tenant list should contact them.

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada has ruled in the past these lists can be illegal, and violate the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act.

The act is Canada’s federal private-sector privacy law, which applies to the collection, use and disclosure of personal information during commercial activities. Personal information includes things like name, income and social status.

Generally, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act requires that organizations obtain “meaningful consent” for the collection, use or disclosure of personal information, Tobi Cohen, a spokesperson for the office of the privacy commission, said in an email.

On the organization’s website, landlords are warned that informal background checks on tenants, like scanning someone’s Facebook page, or consulting another landlord about them, still counts as collecting personal information and must follow conditions of the act.

Even if a landlord believes a tenant has been disruptive or damaged the unit, or had a poor payment history, “this does not give you the right to disclose this information by … contributing to an unregulated ‘bad tenants list,'” says the office of the privacy commissioner, since “vigilante” actions are seldom, if ever, permitted by law.

The office of the privacy commissioner said formal and regulated mechanisms, like credit agencies, may be used in appropriate circumstances.

But that doesn’t sit well with landlords like Paula Hodson.

She runs credit checks, but those won’t tell you whether someone will take care of a unit, Hodson said, and has had major damage done by people who looked fine on paper.

Hodson and her husband own five units in Nova Scotia, including duplexes and small homes, she said. As a member of Landlords Unite, she said she’s contributed names to the bad tenants list.

Although she has posted names publicly in that group before, she now privately messages the group’s moderator to avoid “retaliation.”

Her reasons have ranged from having police over at a unit multiple times as well as being denied rent due to dramatic damage, including buildups of mould and mildew.

In one unit, Hodson said they’ve spent more than $5,300 over the past few months cleaning up after a former tenant who left in April. That includes painting, cleaning, new flooring and appliances.

Without bad tenant lists and group chats between landlords, they would be even more exposed, Hodson said, “because we have nowhere to find out about these people.”

“If people don’t want their name posted, then don’t do all that damage,” Hodson said.

Hodson said having more details available through the residential tenancy board is much needed, like someone’s damage history, which does exist in an American state where she also owns a rental property.

From her perspective, Hodson said the bad tenant list in Landlords Unite is “not public” since it’s a private Facebook group that was only brought to light by ACORN members who should not have been there.

The advocacy group does post public lists of its own, inviting tenants to name their worst landlords annually in a “Slumlord Smackdown.”

Tension between landlords and renters has risen over the last few years as prices go up, Hodson said, but that increase is needed as insurance, appliances and other costs spike, too. She said she and other landlords have received aggressive and “bullying” messages since ACORN’s campaign began.

Wayne MacKay, a law professor at Dalhousie University, agreed that these types of shaming issues seem more prevalent now. He said it is likely accentuated by the national housing crisis and prevalence of social media, where things can be broadcast more widely than ever before in history.

He said while it’s likely fine for landlords to discuss tenants’ history one-on-one like any reference letter, the legal issues come in when those details are posted on social media because that could defame someone’s character generally.

Long lists of names on a bad tenant list without context, put together without giving someone a chance to respond, are especially problematic, MacKay said.

“Perhaps there should be some way of the tenants themselves being informed that they’re on this rogues’ gallery and given an opportunity to try to explain themselves,” MacKay said.

“If you’re going to do this kind of thing, there are perhaps better and fairer ways to do it.”

Kevin Russell, executive director of the Investment Property Owners Association of Nova Scotia, said he was “gobsmacked” when he heard of the bad tenant lists after ACORN’S campaign began.

He said his association operates under the laws of Nova Scotia, and doesn’t participate or associate with any online chat groups.

“Nor do we possess, or ever considered developing, a tenant blacklist and we strongly condemn any organization or a landlord that use such lists,” Russell said.

He added that while most professional landlords are “well-versed” in the Residential Tenancies Act and understand how privacy law plays into what they can and can’t do, there has been a surge in people getting into the property investment industry without fully researching landlord and tenant rights.

“They’ve taken situations under their own control, and it’s gone down the wrong path,” he said.

Russell said the association offers various programs to help property owners, including an “I rent it right” online tutorial that covers which tenant verification processes follow the law.

***

Article by Haley Ryan for CBC News