Capital Current: Ottawa’s affordable housing crisis needs more federal help, experts, activists say

Posted October 7, 2019

While low-income activists urge the city to take immediate action on Ottawa’s affordable housing crisis, policy experts and city councillors are looking to the federal government for some relief.

Posted October 7, 2019

While low-income activists urge the city to take immediate action on Ottawa’s affordable housing crisis, policy experts and city councillors are looking to the federal government for some relief.

While low-income activists urge the city to take immediate action on Ottawa’s affordable housing crisis, policy experts and city councillors are looking to the federal government for some relief.

Released in 2017, the National Housing Strategy (NHS) was designed to increase the portion of the federal budget that would subsidize costs for low-income renters and reduce the burden on people currently spending more than 30 per cent of their income on housing.

The NHS had lofty aims. It would cut chronic homelessness by 50 per cent, remove 530,000 families from housing need, renovate and modernize 300,000 homes and build 125,000 new homes with a budget of $55 billion to be spent over a decade.

But the plan was not universally welcomed.

B.C. economist Marc Lee wrote that “much of the commitment is in the form of loans not grants, is spread over 10-years and is back-end loaded (meaning that most of the money is spent at the end of the 10 years).”

Lee argues that “too much of the media attention has been on home ownership and not enough on providing dedicated, affordable, rental housing.”

According to Counc. Catherine McKenney, the city needs that money now.

A recent report by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) showed that Ottawa is quickly becoming unaffordable for many people. By comparing wages and rental information from Statistics Canada and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) for October 2018, the CCPA calculated how many hours people would have to work at minimum wage (and other wage levels) to be able to afford an apartment, what Policy Alternatives calls a ‘rental wage.’

According to the CCPA, the Ottawa’s average rental rate is the fifth highest in the country, behind Vancouver, Toronto, Victoria and Calgary.

On average, a person in Ottawa earning Ontario’s $14 per hour minimum wage would have to work 75 hours a week to afford an average two-bedroom unit renting for $1,301 a month. Somebody working full-time, 40 hours per week, would have to earn $26 per hour. Someone working at minimum wage would need to work 61 hours for a one-bedroom unit.

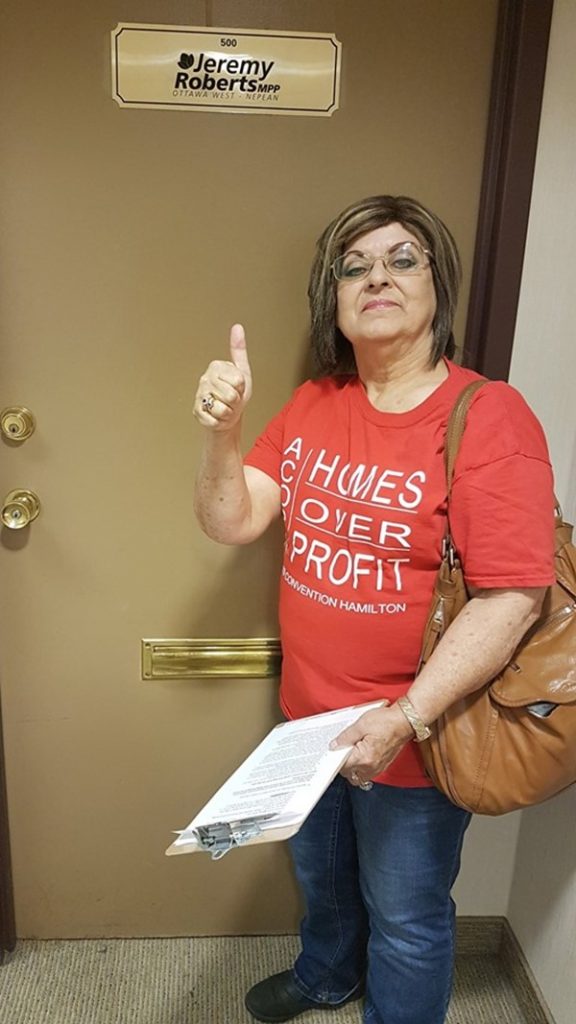

Mavis Finnamore knows first-hand about the underlying issues that surround affordable housing. She was evicted from her home in Heron Gate last year. She now is an activist with the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN).

“We’re trying to prove to [the city] that tenants do need protection from landlords, they do need protection from unaffordable places, places that are full of bugs, places where you expect repairs and you don’t get them,” she said.

Finnamore and ACORN members lead demonstrators in a rally asking for measures including budget increases from the Ontario government for affordable housing outside outside the office of Ottawa West-Nepean MPP Jeremy Roberts.

Finnamore and another ACORN organizer Ashley Reyns delivered a letter to Roberts’ office demanding a meeting to talk about “how his governments’ housing policies were impacting low income tenants.”

“We’re in a fight for our lives to try to keep what we have,” says Finnamore. “There’s nothing that says that [developers] have to build affordable housing, they can charge whatever rent they want. So how the hell is this going to help low-income people?”

Steve Pomeroy, head of Focus Consulting Inc. and a senior research fellow for the Centre for Urban Research and Education (CURE) at Carleton University, is a leading housing policy expert and advisor to many national associations, municipalities, provinces and territories.

Pomeroy said in an interview that while greater housing supply is needed, building alone won’t solve Ottawa’s longstanding housing issue. “That’s not a sustainable solution. It hasn’t been successful in the past; it won’t be successful in the future.”

Pomeroy notes that the city and federal government should focus on tackling supply and affordability as two separate issues.

According to Ottawa’s 10-year Housing and Homelessness Plan, with only 23,000 community housing units in Ottawa and all of them already occupied, another 40,000 units would needed to be built to house all renters in need.

But Pomeroy says “the reality is that 80 per cent of those people who are defined as being in need … live in a house or an apartment that’s in decent condition and it’s the right size for their family, they just pay too much.”

Data from the City of Ottawa Rental Market Analysis published in March 2019 shows that in 20 out of 29 Ottawa neighborhoods, more than 40 per cent of renters are living in unaffordable housing, which is defined as a dwelling where the household spends more than 30 per cent of their income on shelter.

The city supports about 3,500 rent supplement agreements, which provide landlords with the difference in rent for housing-qualified low-and-moderate-income households.

The city has also started providing housing allowances for 300 people on the waiting list for affordable housing, according to Pomeroy.

The potential for the city to provide more of this kind of assistance will increase next spring when the federal government implements a new cost-shared housing allowance program through the NHS, says Pomeroy. “The new plan is expected to increase the budget to allow [cities] to do that.”

A 2019 report by the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) found that despite the fact that municipalities are responsible for nearly 60 per cent of the nation’s public infrastructure, local governments only collect about 12 cents of every tax dollar paid in Canada.

As a result, Pomeroy says “the fiscal capacity doesn’t exist with the municipality to seriously address these issues without some serious help from the federal government.”

McKenney is the special liaison officer for housing and homelessness in Ottawa. Although the councillor has stressed adding inclusionary zoning to the city’s 10-year plan and supports housing allowances, they highlight the need for increased funding from the federal government.

For those spending above the affordability threshold, McKenney says “we don’t need to build new units for those people.” Instead, the councillor says the federal government should aim to reduce the burden of high rental costs.

“Whoever forms government … my hope is that they see that they have to make a serious investment and they have to do it soon. There’s not another demographic that we would tell, who are in crisis, that we would tell to wait four or five years while we sort things out,” says McKenney.

In the federal election, the NDP has promised the largest commitment towards affordable housing, pledging 500,000 new homes in the next 10 years as well as setting aside $5 billion toward affordable housing in the first 18 months after forming government.

The Green party would commit $750 million for new housing units. They propose to set aside another $750 million toward rent assistance for 125,000 households.

The Liberal party plans to focus on higher priced markets like Toronto and Vancouver, tackling affordability issues with their 10-year investment plan of nearly $20 billion.

The Conservative party has a four-point plan to make housing more affordable in Canada. The platform says they will alleviate mortgage stress and inquire into money laundering in the real estate sector.

***

Article by Cara Powell, Liam McCloskey and Polina Gankina for Capital Current