Briarpatch Magazine: What’s at Stake in the Fight for $15?

Posted November 18, 2015

What’s at stake in the fight for a $15 minimum wage

Posted November 18, 2015

On Wednesday morning, April 15, Amelia White left her Scarborough, ON apartment and began her trip downtown. Born in Jamaica, she’d moved with her mother to Lethbridge, AB in the ’70s. It was a lonely time; she remembers being the only black family in the small prairie city. The family soon moved to Winnipeg, where she lived until coming to Toronto five years ago. She likes the city but says she still isn’t used to the crowds.

On Wednesday morning, April 15, Amelia White left her Scarborough, ON apartment and began her trip downtown. Born in Jamaica, she’d moved with her mother to Lethbridge, AB in the ’70s. It was a lonely time; she remembers being the only black family in the small prairie city. The family soon moved to Winnipeg, where she lived until coming to Toronto five years ago. She likes the city but says she still isn’t used to the crowds.A short time later, White was on a bustling Toronto street outside the Ministry of Labour, shoulder-to-shoulder with hundreds of others. The crowd – a mix of union members, students, and activists – was rallying under the banner of “$15 & Fairness,” calling for a higher minimum wage and legal protections to ensure decent work.

“We want $15 an hour so our families can be 10 per cent above the poverty line,” explains White, who earns $11.25 an hour at a local grocery store. “It would help tremendously. I wouldn’t have to worry about the rent or hydro. I can’t afford to do things that I want to do – going to the movies, seeing my friends for coffee. Nothing extravagant.”

White is a member of the Workers’ Action Centre (WAC), a community organization dedicated to organizing low-wage workers, which had planned the protest with a coalition of other groups, including the Ontario Federation of Labour, Health Providers Against Poverty, and the Canadian Federation of Students.

Unions and community groups held similar demonstrations in about a dozen cities across Canada. Worldwide, tens of thousands in over 40 countries participated in the April 15 mobilization. The events were inspired by the “Fight for $15” movement in the U.S., where low-wage workers, especially those in the fast-food industry, have managed to secure a $15 hourly wage in several West Coast cities.

Three weeks later, Canada’s minimum wage movement experienced an unexpected boost. On May 5, Albertans elected an NDP majority, unseating the long-ruling Progressive Conservatives. Premier Rachel Notley quickly reaffirmed her campaign commitment to be the first jurisdiction in Canada to have a $15 minimum wage. As of October 1, Alberta’s minimum wage increased from $10.20 to $11.20 an hour. By 2018 it will be $15.

Irene Lanzinger, B.C. Federation of Labour president, capturing the mood of many progressives in Canada, says that the workers in the U.S. and the changes in Alberta have inspired her organization’s own campaign for a $15 minimum wage. “If these places can do it, we can do it too. We’ve felt like we’ve been part of a bigger, North American or global campaign.”

Dollars and sense

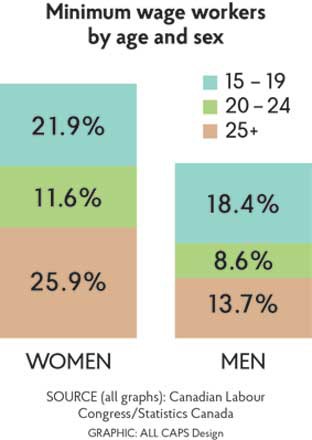

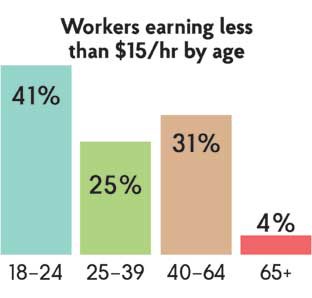

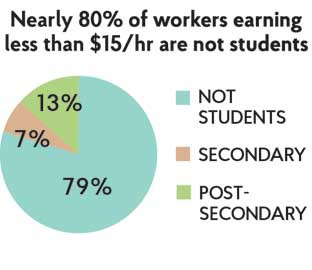

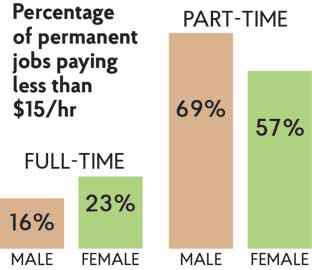

Across Canada, almost seven per cent of workers make minimum wage. Of these workers, more than 40 per cent are under 20 years old. The right-wing Fraser Institute points to these numbers and argues that the issue only concerns “young people still living at home.” But the picture changes when you consider those who are being paid less than $15 an hour. Sixty per cent are 25 or older, and 35 per cent are over 40. Women make up 59 per cent of low-wage workers across Canada. Economist Sheila Block has found that in Ontario, racialized workers are 47 per cent more likely than the non-racialized population to be working for minimum wage; recent immigrants are also disproportionally represented.

“We were promised during our post-secondary education that we would have the ability to have these skilled jobs,” says Caitlin Davidson-King, a member of Unifor Local 3000 and chair of the B.C. Federation of Labour Young Workers’ Committee. “But our future holds minimum wage jobs.”

In Alberta, the Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB) has led the charge against the incoming wage increase. They argue that the raise will result in a loss of between 50,000 to 180,000 jobs, due to increased costs to employers. And, they say, it won’t reduce poverty.

David Green, a professor at the Vancouver School of Economics at UBC and an international fellow at the Institute for Fiscal Studies in London, disagrees. In a study of the economic literature, he found that employment losses as a result of wage gain were focused primarily on teenagers and small numbers of young adults. For those over 24 years old, there was no discernable effect.

“Four years after the B.C. minimum wage increase, employment changed the same as the rest of Canada,” Green says. “In contrast, the Fraser Institute had said that one in six jobs would be lost.”

Across Canada, the gap between minimum wages and the low-income cut-off – the threshold at which people begin to spend more of their income on necessities than the average – leaves many full-time workers substantially below the poverty line.

“You need to raise the wage substantially to address poverty,” says Ian Hussey, research manager at the Parkland Institute, a left-leaning think tank in Alberta.

But now is not the right time, argues the CFIB. Alberta and Canada are in a recession. Employment insurance claims are at their highest levels since 2009, with Alberta and Ontario seeing the largest spikes. The CFIB argues that instead of raising the wage, the government should invest in targeted training programs and offer tax relief to low-wage workers.

“Business will have to make tough decisions in a climate like this,” says Amber Ruddy, director of provincial affairs for CFIB Alberta.

“We are going for the long game here,” counters Green. He explains that increasing the minimum wage has been shown to actually decrease layoffs: employers operating with high employee turnover rates are forced out of the market. “Part of the question is how to design a just labour market. Can we find a way to induce bad employers to use a better model?”

South of the border

Since the first walkout of fast-food workers in New York City on November 29, 2012, the U.S. “Fight for $15” movement has pursued a strategy of one-day public mobilizations targeting low-wage employers. Unlike a strike, the workers haven’t aimed to shutter their workplaces; they’ve focused instead on mobilizing large numbers of people to put public pressure on employers and governments.

As in Canada, workers in the United States are protected from employer reprisals for trying to organize a union. In addition, the National Labor Relations Act protects activity by non-unionized workers who are engaging in “concerted activity,” when two or more employees take action “for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” This broad protection may be a key element in their fight.

“There is no equivalent [in Canada] to protection for ‘concerted activity’ on the part of workers unless it’s in the context of forming a union or association,” says Adrienne Telford, a Toronto lawyer who specializes in labour and constitutional law.

Notwithstanding the recent New York State wage board recommendation to set fast-food workers’ wages at $15 per hour, all of the minimum wage victories have been won at the city level. Cities are fertile ground for wage-hike organizing. In Los Angeles, for example, where city council passed a $15 minimum wage in May 2015, it’s estimated that half of all workers earn less than $15 an hour. The cost of living is higher for all residents in urban areas, low-wage or not, opening up the possibility of wider sympathy for a pay increase. And political representatives are near at hand. But in Canada, cities don’t have the constitutional authority to legislate a minimum wage – provinces and territories do.

It was a municipal ballot initiative that brought forward the first $15 minimum wage in North America, in the small city of SeaTac, 22 kilometres south of Seattle. In about half the country, supporters can collect a prescribed number of signatures and have a “ballot measure” presented to the voters at large in the next election, similar to a referendum. If it passes, the measure becomes law.

Activists in Canada may not be able to use the same tools. In most provinces, referendum results are non-binding, and excluding Saskatchewan, it is only the government, not eligible voters, that can put forward a referendum question.

The fight in SeaTac and Seattle

“The SeaTac campaign was not initially a wage campaign. It was an organizing campaign,” explains Jonathan Rosenblum, former campaign director for the SeaTac airport organizing campaign for the Service Employees International Union (SEIU).

The campaign began by tackling unfair supervision, health and safety issues, and religious discrimination against Muslim workers. These small interventions built people’s trust in each other, and their confidence in collective action.

“After employers refused union recognition, the workers brought forward a ballot vote for a $15 minimum wage,” says Rosenblum. “They were saying: if you won’t negotiate with us, then we’ll go to the voters and have them impose our demands on you.”

On November 5, 2013, voters narrowly approved the ballot initiative, which raised the wages of 6,300 transportation, hospitality, and fast-food workers at the SeaTac airport and related businesses. An employer-led legal challenge succeeded in limiting the number of workers covered by the $15 wage, but on appeal, the Washington State Supreme Court upheld the original terms of the wage increase.

Around the same time, Kshama Sawant, an avowed socialist, was elected as a Seattle city councillor. She had called for a wage increase, as had the successful mayoral candidate, Ed Murray. On June 2, 2014, Seattle city council unanimously approved a $15 minimum wage, to be phased in by 2018. In a concession to employers, for the first few years, people who receive tips and health benefits will have to count them against their wages. Soon other cities were following their lead. San Francisco voters approved a $15 ballot measure in the fall of 2014, and Los Angeles city council voted in an increase in May of this year.

“We have shifted the conversation. Wage gains have become politically achievable in this environment,” says Rosenblum of the minimum wage movement. But, he cautions: “That’s not an upsurge in worker power, but an indication of where the politics of the country are at.”

Now those politics have drifted north, to the benefit of about 250,000 low-wage workers in Alberta. The struggle has even registered nationally, with NDP Leader Thomas Mulcair calling for a $15 hourly wage for federally regulated employees.

Building the movement in Canada

The story has been different in B.C. and Ontario, where the mobilization for $15 an hour is an evolution of previous minimum wage campaigns, led not by politicians, but by worker organizations, community activists, and unions.

White was involved in the 2011 Ontario campaign to raise the wage to $14. She remembers the moment Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne announced the $11 wage. The WAC, which had built momentum through a series of monthly actions held on the 14th day of each month, was invited to the press conference. At a downtown coffee house, the premier, flanked by Minister of Labour Yasir Naqvi, explained that the increase was all she could do for now. It wasn’t good enough for White.

“You try living on $11 an hour,” she’d told the premier. “She doesn’t understand,” says White. “She couldn’t say anything against it. I was celebrating about that for a week.”

Such moments, where workers are able to speak truth to power, can help keep spirits up. But how can a movement build the power, influence, and momentum needed to achieve its goals?

“We have an ongoing, membership-driven process,” says Karen Cocq, a staff organizer with the WAC. The Centre has played a leadership role in the provincial network and is supporting groups to take part in the provincial review of Ontario’s labour laws. But they remain committed to building their membership base of workers in low-wage and precarious jobs. “We hold regular meetings with our members to build political analysis. Members are coordinating other members to do outreach, gather petitions, and other campaign work. Our members inform our direction, including our involvement in the ‘Fight for $15 & Fairness.’”

Only a handful of grassroots groups in Canada have the funding to organize low-wage workers: the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty, the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now, and the Immigrant Workers Centre in Montreal. The labour movement has supported (and, in some cases, led) the minimum wage campaign, but unions here have not made an investment on the scale of their American counterparts.

SEIU, one of the largest unions in the U.S., has contributed $23 million to the “Fight for $15” campaign in 2014 alone, primarily by funding local community groups that organize with workers, such as New York Communities for Change and Working Washington in Seattle.

Anti-union groups such as Worker Center Watch have seized upon the numbers, characterizing the minimum wage fight as a “Ponzi scheme” that wastes union members’ dues on employing “rent-a-mob” worker centre activists.

Some on the left have also criticized the effort, suggesting that labour management is not only putting up the money, but also pulling the strings. Arun Gupta, writing in Counterpunch, points to the involvement of the public relations firm BerlinRosen, arguing that instead of training workers to build power on the shop floor, SEIU’s leadership is focused on creating a powerful image for the media by maximizing single-day turnout and using “compelling visuals, stories and a narrative.”

“Without the resources of my union we wouldn’t have seen these gains. But equally, these fights would not have taken off without grassroots support for them,” says Rosenblum. “You need workers to act collectively and demonstrate the cost of not doing the right thing. You can’t do that just through dollars, but with grassroots organizing with people.”

A number or an idea?

Gloria Yogyog spends her weekday mornings outside a Vancouver SkyTrain station, offering bleary-eyed commuters a copy of a free daily newspaper. The job, just 15 hours a week, pays $10.50 an hour. On her off-hours, Yogyog is happy to keep handing out flyers, but these are for ACORN and the minimum-wage movement. She’s been an active member of the community group since 2010, working on campaigns for better housing and for banks to lower fees on remittances sent by workers to family overseas.

“People are happy to support us,” says Yogyog, who struggles to pay her $920 monthly rent with income from the paper, sporadic cleaning work, and her disability benefits. “Everybody is happy to have their wage increase.”

Yogyog, and White in Scarborough, stand to benefit directly from a higher minimum wage. But they know the fight won’t be easy, and that they can’t do it alone.

“I ask workers if they know their rights, if they have any problems,” says White, who is a senior leader at WAC, and spends her Thursdays at the Centre making phone calls and assisting with workshops. “It’s not you alone, I tell people. Your kids will get more money, have a better life. We can fight to change the law to make it better for workers.”

The demonstration in Toronto on April 15 was not White’s first in front of the Ministry of Labour, a frequent target of workers’ protests. But the day ended differently than at previous protests. Together with Cocq and members of WAC, White boarded a bus headed for the airport. Workers from the Toronto Airport Workers’ Council were rallying outside the departure lounge, calling attention to contracting out and low wages. Many of them work for less than $15 an hour. WAC is hoping to build on this new relationship, strengthening the fight for wages and decent work.

Hours later, White begins the long trip from Pearson Airport in Mississauga to her home in Scarborough. “It was a good day,” she says.

“To build a movement, you need a big idea. Fifteen [dollars per hour] is a big idea,” says Rosenblum, reflecting on a movement that has ballooned since the first victory by airport employees two years ago. “But fifteen is just a number. How can we meet people’s basic needs, but also their aspirations?”

***

Article by Yutaka Dirks for Briarpatch Magazine