The Globe & Mail: New Brunswick moves to cap rent increases in effort to cool frenzied housing market

Posted March 24, 2022

Posted March 24, 2022

New Brunswick plans a variety of changes to cool its frenzied housing market, including a retroactive limit on rent increases that would see landlords reimburse some tenants for excess payments.

The provincial government, which projected a small surplus of $35-million in Tuesday’s budget, said that rent hikes would be capped at 3.8 per cent for 2022, dating to the start of the year.

After updating its tenancy legislation in December, the province is planning to do so again, barring landlords from ending a lease without cause, among other changes. New Brunswick will also phase in a 50-per-cent reduction in property tax rates for rental housing, a previously announced move that was delayed by COVID-19.

The Maritimes have been experiencing a pandemic-fuelled influx of new residents, leading to its strongest population growth in decades – but also, considerable stress on its housing infrastructure.

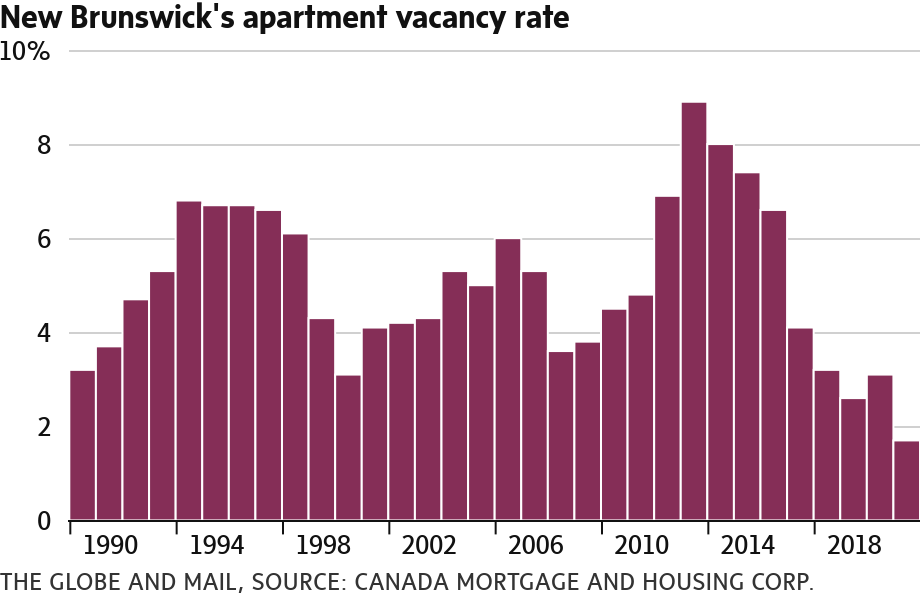

The vacancy rate for purpose-built apartments in New Brunswick was 1.7 per cent in 2021, the lowest since at least 1990, according to figures from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp.

Furthermore, the province has seen rent inflation of 9.5 per cent over the past two years, second only to Prince Edward Island, where rents have soared 19 per cent, as measured by Statistics Canada’s consumer price index.

The governing Conservatives have opposed bringing in rent control – that is, annual limits on rent increases – saying it would slow the construction of needed apartments. Its stance had differed from that of jurisdictions which froze rents early in the pandemic or brought in temporary rent controls to protect tenants.

However, the province changed its tune on Tuesday, recognizing the continuing stress in rental housing.

“While we are confident that the market will catch up with demand … our government acknowledges that more needs to be done for renters,” Finance Minister Ernie Steeves said in prepared remarks.

“Failure to address these challenges will also put pressure on our labour force,” he added.

The rent cap should allow some renters to recoup money. For instance, if a tenant’s monthly rent was increased to $1,200 from $1,000 on Jan. 1, her rent would be rolled back to $1,038. She could then deduct $486 – three months of excess payments – from future rent. If that individual moved out on March 1, the landlord would be required to reimburse her for two months of excess payments, or $324.

Tuesday’s measures drew a mixed reaction from tenant advocacy groups. While they applauded the move to curb rent growth this year, they also said it was a temporary move that arrived after years of escalating costs.

“This is a government that has been playing from behind in this crisis,” said Matthew Hayes, a founding member of the NB Coalition for Tenants Rights.

Many New Brunswickers have been hit with sizable rent hikes in the pandemic, usually with little recourse to challenge them. The Globe has spoken with several tenants in the province this year who saw their rents raised by hundreds of dollars a month, often shortly after ownership of the building changed.

Apartment buildings have become a sought-after asset class in Canada, owing to decades of meagre construction and robust population growth, putting upward pressure on rental rates. In many provinces, it is fairly easy to evict tenants for the purpose of renovation, which can be used to raise rents even more.

New Brunswick changed its tenancy legislation in December to allow all tenants to dispute rent increases they felt were excessive. Previously, only tenants who had lived in a unit for at least five consecutive years could do so.

Once the 2022 rent cap expires, any increases must be at the same percentage for comparable units in the same building, or the rent hike must be “reasonable” compared with similar units in the “same geographical area.”

Housing advocates say that language is open to interpretation and falls short of the standards in provinces that prescribe a maximum percentage increase for rents each year, often tied to broader inflation.

The proposed rules around evictions are too little, too late for Nichola Taylor and her family, who live in Fredericton. Ms. Taylor was served with an eviction notice in February, not long after the building was purchased. (The notice did not provide a reason – which would be illegal under the incoming rules – although the property manager said it was for renovations.)

Ms. Taylor quickly pounced on a new apartment – albeit, one that costs her family an extra $300 a month.

“There’s nothing we can personally do” about the eviction, she said. “On the other hand, it’s a small step in the right direction for tenants.”

***

Article by Matt Lundy for the Globe & Mail